You can't build that here

Pressures on the Upper Valley's housing market have been growing for decades.

Much of the recent history of eastern central Vermont — an area spanning Orange and Windsor counties with Norwich, Thetford, Hartford and Woodstock as its foci of settlement — was influenced by the presence of Dartmouth College across the river in Hanover, New Hampshire. Dartmouth College was founded in 1770. Francis Lane Childs wrote in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine in 1957, “It is hard today surrounded by all these modern buildings, streets, lawns, to realize what this land was like. All this plain was covered with a virgin forest of huge white pines. Some of them when cut were measured and proved to be actually 270 feet in height with a distance of a hundred feet from the ground to the first branch.”

While Dartmouth has often been referred to as a college in the wilderness, a lot has changed in 250 years. The college slowly expanded, but a change perhaps more relevant to the need for housing was the spate, starting in the 1960s, of high-tech engineering “spin-off” companies, often founded by faculty at Dartmouth’s prestigious Thayer School of Engineering. They include Creare founded in 1961, Creare Innovations (now Fuji Dynamics), Luminescent Systems, Verax, Fluent, Thermo Dynamics, and Hypertherm founded in 1968. The change accelerated in the last few decades, with the Upper Valley becoming a hub for biotech startups as well. In 1989, Dartmouth entered the real estate business with the Centerra Business Park joint venture that would offer as much as 760,000 square feet of retail, office, industrial, and research and development space. In the previous year, 1988, Dartmouth had also begun the development of the new Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, which opened in 1991. Today it has around 8,000 employees.

An interview in Business NH Magazine with Julie Demers, executive director of the NH Tech Alliance, read, ”One possible challenge, however, is a workforce shortage.” While this was written recently, it would have been an equally appropriate sentiment for the 1980s through the 1990s.

However, a workforce did come to the Upper Valley, bringing with it a boom in subdivision and home construction. While the Upper Valley may not have offered the biggest salaries in the US to doctors and engineers, money alone was not the sole draw. Skiing, along with other tourism, was part of a long-concerted effort in northern New England to offset a dwindling agricultural economy. To many, a high-tech job in a rural setting that offered skiing and other outdoor recreation was extremely attractive.

I remember in the 1990s-2000s there was a lot of venture capital flowing into the area. There was a boom in investing in biomedical startups and engineering startups, all created by faculty at Dartmouth. In my experience as someone who was on faculty search committees, the Dartmouth recruits were usually in their mid-30’s to early 40s, married with small children, looking for a place to establish their career and settle down. Many of them built new houses.

—Thetford resident

Interstates were built in Vermont between 1957 and 1978, and construction of Interstate 91 between Norwich and Bradford began in 1970 and was completed in 1972. These new highways were a contributing factor that facilitated the influx of new people. Not only did they enable tourists and skiers to flock to Vermont in ever-increasing numbers, they also reassured workforce newcomers that they were still connected to urban areas like Boston and New York City. Furthermore, interstates made it convenient to own a vacation home, often in a ski area, further encouraging a second home trend that was already long-established in Vermont. To provide additional attractions, ten new state parks sprung up in Vermont between 1958 and ‘68, and visits to state parks soared in the same period from 2,600 to 126,000/year.

While high-tech job opportunities were multiplying in the Upper Valley, a Vermont state commission found in 1968 that Vermonters “overwhelmingly wanted to protect its unique community and natural resources.” Some of this was sparked by alarm over “hastily constructed” second homes that were springing up around ski areas. According to an interview with Republican Governor Deane Davis, “we found open sewers running into ditches… even the real estate men who were engaged in the business of selling lots were deeply concerned.” Act 250, one of the first programs in the US to regulate land use, was passed by a conservative legislature under Governor Davis in 1970. “Act 250 is significant because it gives citizens (existing landowners) an opportunity to participate in decisions regarding large-scale development projects and requires communities to consider the long-term impact of such projects.“

In Thetford, Crossroad Farm sits on land that was once proposed for housing (including affordable housing) in the 1980s. If successful, it would have seen 66 houses, including duplexes, scattered over 100 acres. The Act 250 District 3 Environmental Commission blocked the project not once, but twice. If it had not, Crossroad Farm would not exist today.

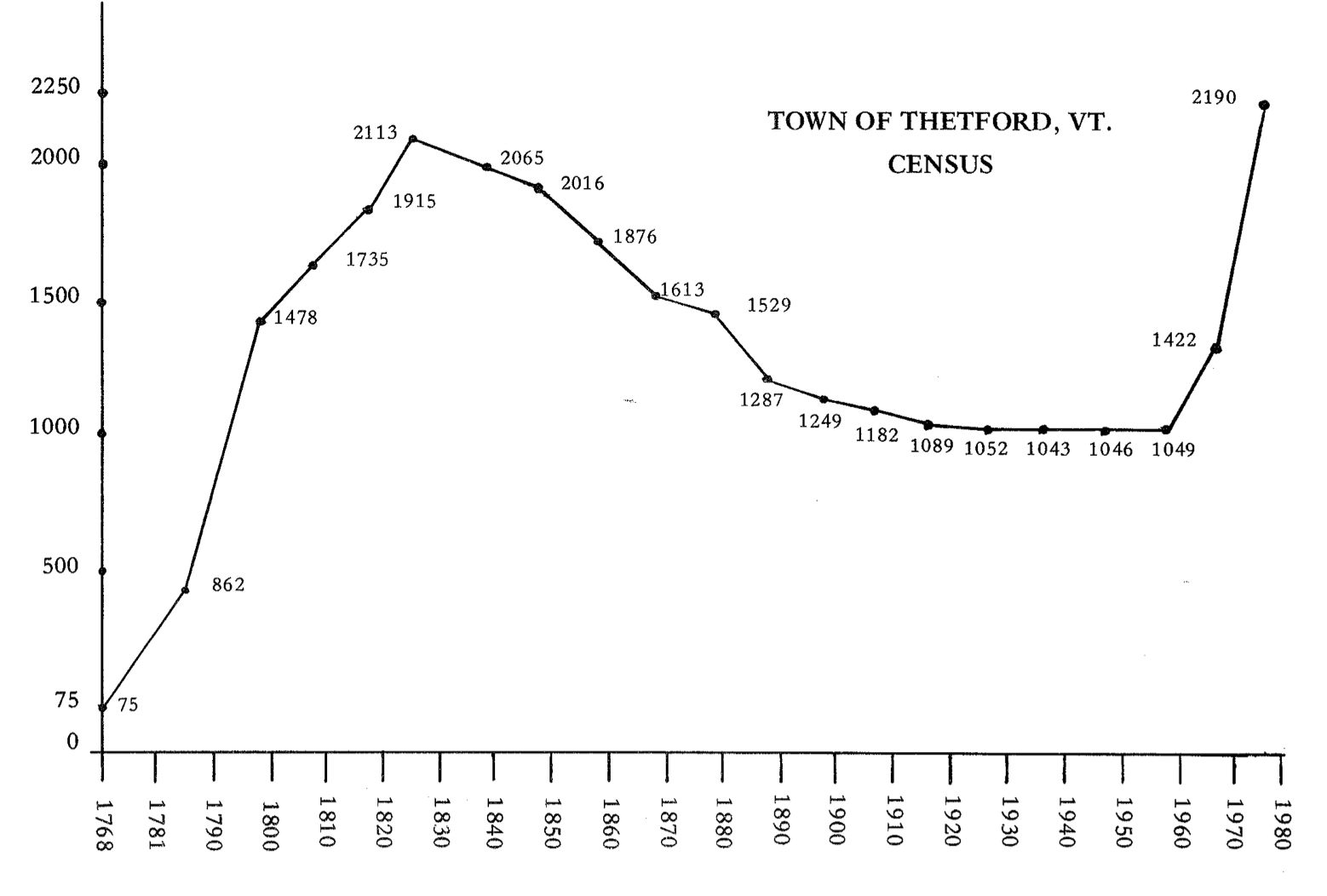

While Thetford had adopted zoning bylaws around 1973 (the first year we could find a Zoning Report in the Annual Town Report), shortly after the completion of the highway, the regulations at the time weren’t restrictive enough to stop all developments. While large projects like those slated for Crossroad Farm could be blocked by Act 250, smaller ones were not. Indeed, development in Thetford boomed along with the region. The 1980 Town Report included a graph overviewing Thetford’s population growth:

Thetford’s population doubled in the 1970s and ‘80s, seeing over 450 new residential constructions. In the ‘80s, the community even considered the construction of a middle school to help ease the burden on its over-enrolled school system, a prospect that might seem alien in today’s culture of low enrollment and school consolidation.

The number of residential parcels in Thetford increased by 337 between 1980 and 2005, from 651 to 978, or 50%. While the annual Listers’ Report stopped providing parcel data in 2005, it’s clear from other sources that new development dropped off nationally after the 2008 housing crisis. As VPR reported, “Back in the 1980s, Vermont was building more than 3,000 homes each year. In the most recent decade, that number was down to 400 each year...” One source indicates there were only 7 new constructions in Thetford between 2010 and 2020.

Simultaneous with the increase in new parcels, from 1982 to 2012, Vermont lost 322,728 acres of farmland, a 20.5% decrease and the largest share in all of New England. It is no wonder the state, regional, and local planning officials advocate for conserving natural resources and stopping the parcelization of open land. Instead, from state planning statutes to Thetford’s Town Plan, every effort is now being made to direct new development into village areas and to discourage rural sprawl.

Ironically, however, some of the state’s best agricultural soils are in village and town centers, which had been obvious settlement locations throughout Vermont’s colonial history. This puts the state’s development goals at odds with the reality on the ground, demonstrated clearly by the parcel the Town recently purchased – and then sold – in Post Mills for housing. The parcel, while technically developable and meeting the state’s requirements, would have permanently developed important agricultural soils. Other notable properties, such as the open expanse of the Post Mills Airport, sit on similar important soils and shouldn't be further developed.

A lot of fingers are pointed in trying to understand the housing crisis of today (locally and nationally), from investment banks buying up single family homes to seniors aging in place rather than moving in with family like generations of old, or downsizing and freeing up their home for a family with kids, to buyers making all cash offers. Zoning and nimby-ism, the cost of materials, and the labor shortage in the construction industry are also often cited. Gov. Scott noted in January that Vermont’s workforce has declined by 24,000, “That 24,000 is larger than the population of every city and town in Vermont other than Burlington.”

Second home ownership has also been cited as contributing to scarcity and driving up property prices. Vermont ranks second in the nation in percent of housing stock used for second homes, about 17% according to research by Digital Third Coast. That amounts to 58,000 homes.

Whatever the cause(s), one thing does seem clear: younger, working, and first-time homebuyers are being priced and bid out of the housing market in Thetford and the Upper Valley. They are barred from the rampant development practices of a few decades past where forests and farms were gladly fragmented to make way for a migration wave of in-bound young professionals.

The list of places where it is unsuitable to build is getting longer, and perhaps rightfully so. Steep slopes, forest blocks, wetlands, and agricultural land all enjoy varying degrees of protection in Thetford, but what does that leave? It is wise to protect our natural resources, but to those looking to call Thetford or the Upper Valley home today, to enroll their kids and work and shop at area businesses, opposition to housing development is one more example of a privilege afforded to prior generations that no longer exists today.