How Vermont became a destination

In 1911, the Vermont legislature mounted a full-fledged campaign of tourism promotion.

The influx of in-bound homebuyers to Vermont and the Upper Valley during the COVID-19 pandemic had a large and well-documented impact on the housing market, decreasing availability and raising costs both to own and rent in the region. This isn’t the first time that Vermont has been a destination for those fleeing the stresses of the world.

Between 1906 and 1920 Thetford, Fairlee, and West Fairlee saw a sudden surge of summer camp development on Lake Fairlee and In Thetford Center. Roughly a half century later, Vermont experienced a rapid and large influx of young people, often from urban areas. This so-called “hippie invasion” of the mid-1960s later melted into the era of the “yuppies” (young, upwardly-mobile professional people) who became a dominant influence both in Vermont and in the bi-state Upper Valley region starting in the 1970’s and 80’s.

Population shifts and cultural change in Vermont began even earlier, however. They have actually been occurring for well over a century. A flashback to the early 1800s finds settlers who were subsistence farmers moving from hill farms into the valleys. While hilltops were less swampy and more easily cleared, advances in farming technique and mass tree felling permitted the more fertile valleys to be exploited. What followed was a gradual change from mere subsistence to production of agricultural surplus.

In particular, wheat rose as an important crop, and the Connecticut River Valley became known as the breadbasket of New England. Transportation was also improving, and new turnpikes allowed goods to be shipped to urban markets that lay to the south.

Another agricultural phenomenon was the rise of sheep farming for wool. The invasion of Spain by Napoleon in 1808 had resulted in the release of hitherto jealously guarded merino sheep to other countries in Europe. Some of the merinos were exported to the US, thanks to William Jarvis, an American diplomat in Portugal. Jarvis later bought a farm just south of Bellows Falls, VT, where he kept 200 of the sheep. Because Vermont had been denuded by the hill farmers, he distributed merino sheep here to use the open spaces. Thanks to their top-quality fleece, the wool industry grew at a phenomenal pace, as did more deforestation. Wool was the main Vermont industry in 1820, and the population of Vermont doubled between 1800 and 1850.

However, in 1846 the tariff on wool that protected Vermont’s production was abolished. In addition, the construction of canals in Ohio and Pennsylvania allowed cheaper Midwestern wool to compete for urban markets. By 1870 there was too much wool production, resulting in mass sell-offs of sheep in Vermont.

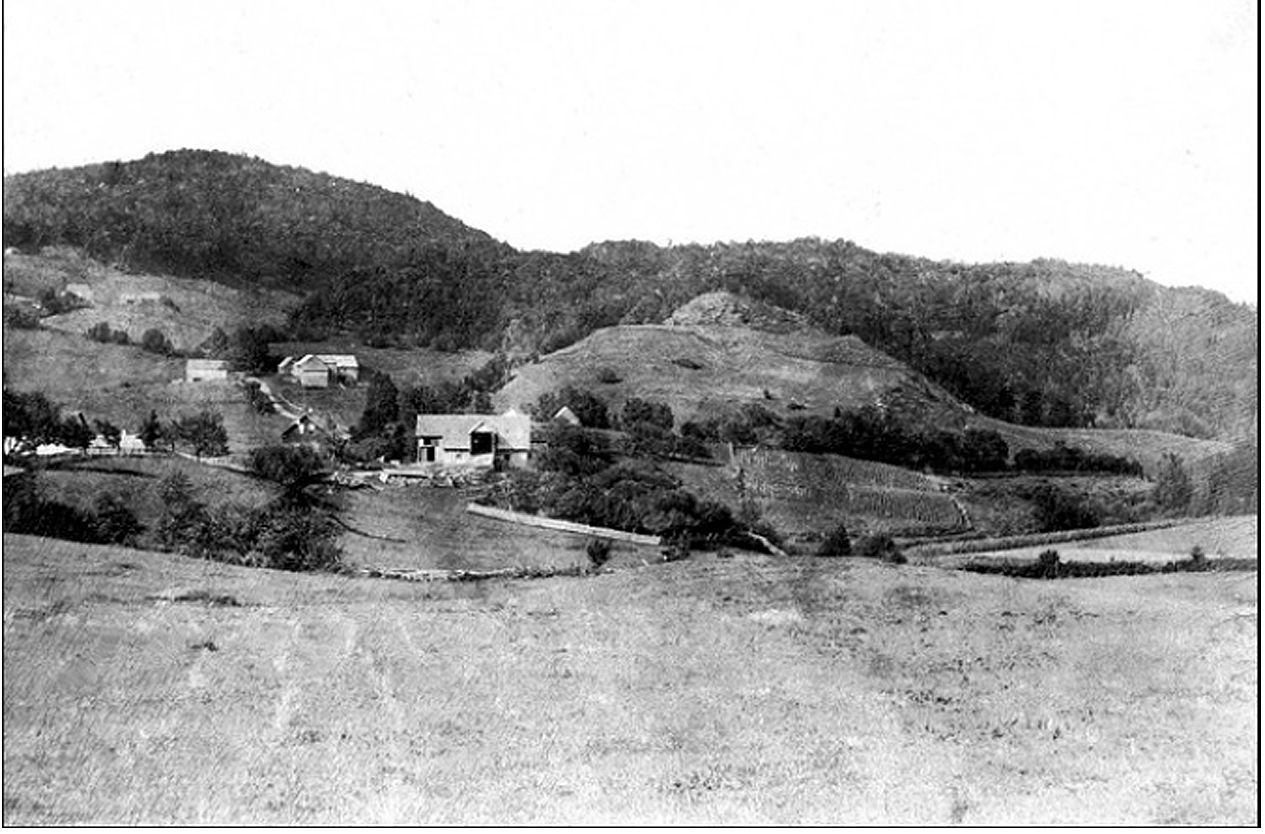

In the late 1800s, the Vermont legislature was concerned about the growing number of abandoned hill farms and the exodus of young people from the state. Not only were sheep no longer profitable, Midwest competition caused Vermont wheat production to decline by 92% and corn production by 30%.

In spite of the fact that dairy in Vermont was on the rise, many young rural people didn’t see a future in farming. Furthermore, the building of Vermont railroads that began in 1845 provided a means to escape, either out west or to cities, in search of better opportunities. From 1880 to 1910, the number of farms, particularly hill farms, declined by 2,813. The census for the years 1880 and 1890 showed that while the national population grew by 25%, Vermont grew by less than 1% in both decades.

Alarmed, the state tried various ways to lure new residents, particularly farmers, to Vermont. They printed farmland maps in Swedish, hoping to attract farmers from Sweden, who were desirable, being European and white. In contrast, French Canadians were less welcome. Repopulation via Sweden was essentially a failure. However, help came in the form of a new climate of national concern about industrialization and rapid urban growth. Vermont began to look at encouraging summer visitors, rather than farmers, as a way to stimulate the economy and the population.

Indeed, New Hampshire, New York, and Maine had already capitalized on the public passion for wild scenery that embodied “loftiness, grandeur and majesty,” typified by the White Mountains, Mount Desert Island, and the Adirondacks. By comparison, Vermont “was not a highlight on any American Grand Tour.” The New York poet, Will DeGrasse, even proposed that the Green Mountains should, in fact, be named “The Green Hills of Vermont.”

Rather than competing for “grandeur,” Vermont focused on the perception of rural areas as a repository of “time-honored traditions upon which the United States was built,” offering a stark contrast to the dirt, crime, and corruption associated with cities. The 1890s saw pamphlets issued by the State Board of Agriculture and Central Vermont Railroad advertising Vermont as a wholesome escape from urban “heat, dust and disease.” They stressed the gentle and pastoral beauty of Vermont, while touting its modern conveniences like telephone, railroads, free mail delivery, and co-op creameries. It was a landscape that, in spite of being tamed, had retained its wildness. In 1911, the legislature mounted a full-fledged campaign of tourism promotion.

It is probably no coincidence that this era, with its growing fear of big cities, saw the development of many summer camps, such as in the Thetford-Fairlee area. While the national trend was camps for boys, these camps were groundbreaking in that they catered mostly to girls from cities. On Lake Fairlee these included Billings (1906), Beenadweedin (1908), Ohana (1911), Norway (1912), Kenjocketee (1912), and Lochearn (1814), and in Thetford Center Campanoosuc (1907), Camp Hanoum (the Singing Camp, 1910) and Kokosing (1920) . A Rural Planning document from 1931 notes that “the incomes of many Vermonters are substantially increased by revenues from the camps.” But what planners really hoped was that campers would “learn to love Vermont'' and return to become summer residents.

It should be noted that, starting as far back as the mid-1800s, second home ownership had quietly proliferated. One form was in the “gentleman’s farm”—projects of wealthy individuals who often liked to showcase the latest innovations in farming practice. Affluent urbanites also fell in love with Vermont’s lakes, and summer enclaves developed where people hosted glittering parties and cultural events of all sorts. The visitors arrived by train, were transported to their cottages for the summer, and returned year after year. The coming of the automobile in the 1920s put tourism in reach of growing numbers of people. In response, hotels, guesthouses, and tourist cabins multiplied throughout the state. Each village in Thetford had at least one inn, for example the Commodore Inn in Post Mills and the Porter Tavern in Thetford Center.

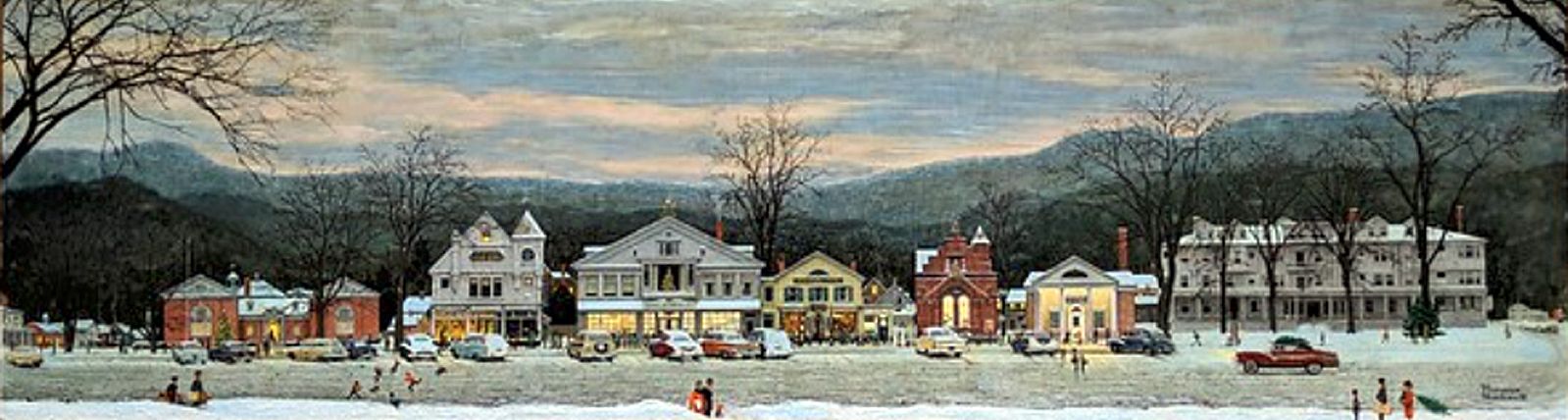

By the 1940s, the selling of Vermont as a tourist’s dream had become a major part of the economy, one that remains to this day. It was aided by the rapid growth of the ski industry. In fact, Vermont skiing was featured in the popular movie “A White Christmas.” The state’s cultural image was also burnished by well-known artists and writers who moved here — the Von Trapp Family, Norman Rockwell, and Robert Frost, to name but a few. Many will remember writer and activist Grace Paley, who summered in Thetford and lived the last 10 years of her life here, and whose husband, the writer Bob Nichols, donated the land for the Thetford Fire Department.

While tourism, artists, and summer homes brought in new people and new ideas, another influence that may have contributed to cultural shift began in 1932 when Helen and Scott Nearing, famous pioneers of the “back to the land” movement, purchased a farm in Winhall, VT. Scott Nearing was a proponent of economic equality and socialism. He was outspoken against the 1914 war, resulting in an indictment under the Espionage Act. The Nearings espoused and taught self-sufficiency in Vermont for two decades before moving to Maine. Their book Living the Good Life, How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World resonated with many and inspired a serious interest in moving to Vermont to take up homesteading.

That same period saw the founding of the non-mainstream Goddard College, in Plainfield, VT, in 1939, on what had been a large gentleman’s farm owned by the Martin family. Here, students and faculty cooperatively aimed to build a democratic community based on the mission of “plain living and hard thinking.” Throughout the 1960s, Goddard was a magnet that attracted those seeking alternatives to “traditional cultures and lifestyles.”

In retrospect, recent immigration to Vermont didn’t just happen out of the blue. It seems that the foundations had already been laid over a century before. Stay tuned for Part 2, where we’ll explore the impact of the population shifts on housing development.