The changing of the guard

Are we ready to grace our informal and picturesque backroads with bright, shiny guard rails?

It’s hard to ignore the shiny, pristine guardrails flanking stretches of newly-rebuilt Route 132 in Thetford. And if drivers aren’t moving so fast that they blur their surroundings, they might notice that the guard rails look a little higher than they used to be. Indeed, there has been a quiet evolution in guard rail design, especially since the 1990s.

Historically, Vermont began requiring road guardrails in 1899, when horse-drawn transportation was the norm. The state passed an Act, requiring “towns to erect and maintain suitable guards or railings at all dangerous places on public highways to protect travelers from running over or down embankments…” However, “a person injured by reason of a town neglecting to maintain a railing at a dangerous place… was not entitled to recover against the town, under such Act, for damages resulting therefrom (Moody vs Town of Bristol, VT).”

Back then, Vermont had few paved roads. As late as 1943, only nine percent of the state’s 14,000 miles of roads were paved. About half of the remainder were gravel, the rest, earth. In the early 1900s, automobiles were a curiosity, until the advent of Henry Ford’s motorcar in the prosperous 1920s. After that, the increased numbers of automobiles and their speed spurred guardrail construction throughout the U.S. The American Road Builders Association in 1931 described guardrails of the day. The list included boulders, wooden posts, planking, logs, wire cable, woven wire, steel bars, steel plates, reinforced concrete, stone walls, and earthen embankments. The single-minded goal was to stop vehicles from running off the roadway. The damage to a vehicle and its occupants from striking such guardrails seemed of little concern. (Seatbelts were not introduced in the U.S. until the 1960s).

There appear to be few studies on effectiveness of these various guardrails, except one in 1928 in which trucks and automobiles coasted down a wooden ramp and collided with cable-and-post guardrails set at various angles. The takeaway message from the study was that all parts of a guardrail system needed to be equally anchored for it to withstand the shock of an impact.

In 1933, the first Highway Guard Rail was patented by Samuel R. Garner. It defined a “resilient” means of supporting the guardrail, and provided a way for the railing to slide on the posts to absorb the impact of a vehicle. This design spawned various guardrail systems, all using steel railings, aka beams, that were W-shaped in cross-section. The W-beam is used to this day. It was readily manufactured by rolling sheet steel. It was strong and relatively inexpensive and could “grab” the bumper of a typical vehicle to keep it from going over the guardrail.

In the 1960s, the guardrail design that came into favor un the eastern US was the one dubbed the “weak-post” design because the W-beam was mounted on “weak” wooden posts. It was adopted because crash tests in the early ‘60s showed that the previously popular “strong-post” design caused damaging deceleration to a vehicle striking the guardrail. More evidence came from the State of New York’s analysis of two years’ worth of road accidents. It found that strong-post crashes were 3.3% fatal with 15.8% hospitalizations, while weak-post crashes were 1.9% fatal with 10.8% hospitalization. In the weak-post system, the posts were only intended to hold the W-beam in position. Upon vehicle impact, the beam separated from the posts but kept its contact with the vehicle, restraining it until it came to rest. However, in some cases the W-beam would fail to disconnect from the posts. If the posts broke and fell, they pulled the guardrail to the ground, allowing the vehicle to shoot over the top.

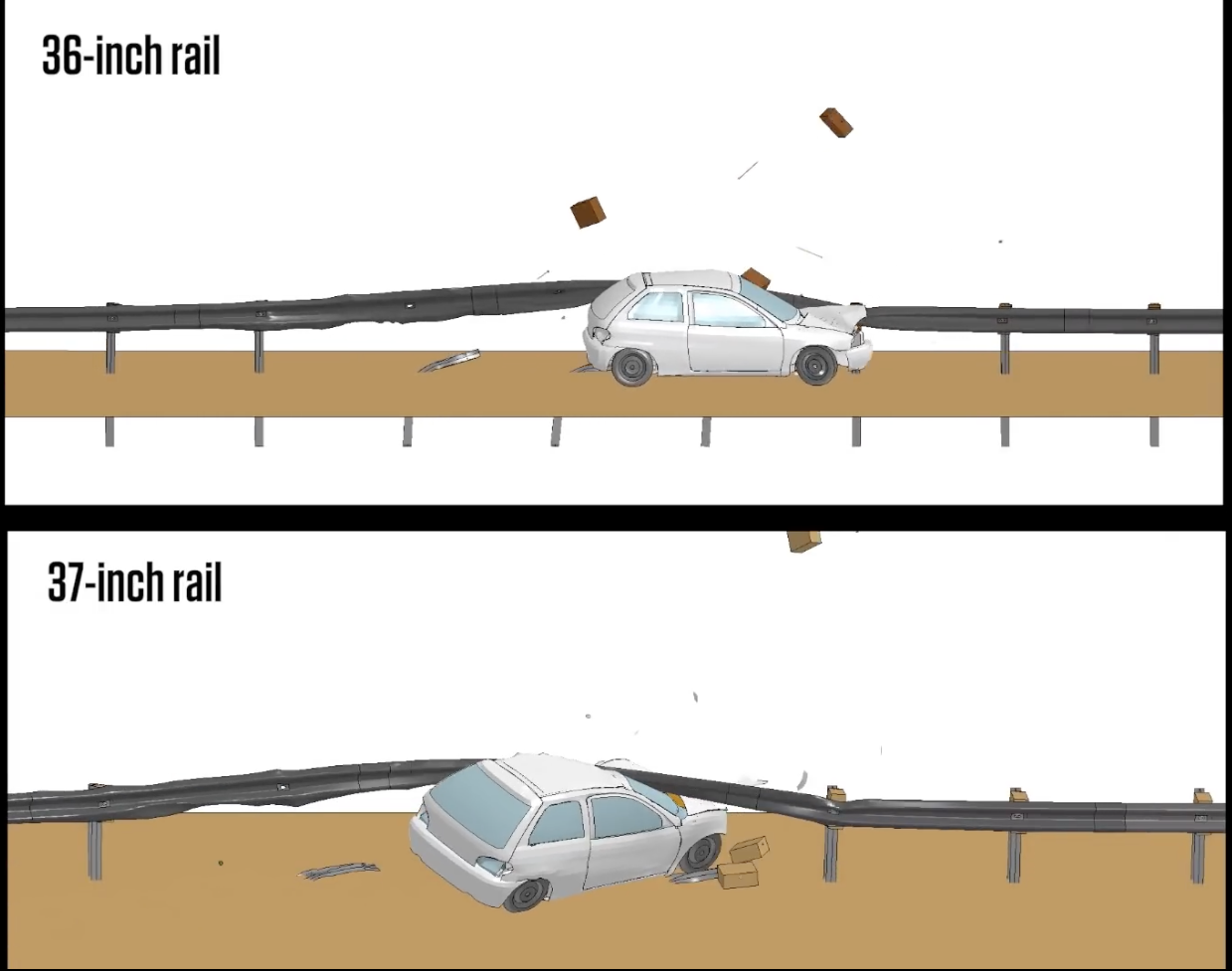

That was in the 1960s through 1980s, when cars were predominantly sedans. But vehicles changed over time. By the 1990s, affluent baby boomers were switching to sport utility vehicles that embodied practicality with ample room for families. Pickup trucks also increased noticeably in overall size and height. The crash testing of highway guardrails changed to accommodate these trends in vehicle size and power. The specification for the “small design (crash) test vehicle” increased from 1,800 lbs to 2,425 lbs. The weight of a “large design test vehicle” changed from 4,410 lbs to 5,000 lbs, with a center of gravity height of 28 inches.

Accordingly, guardrail designs switched back to strong-post designs, with bigger posts and the addition of “blockouts” — literally blocks of wood that spaced the W-beam away from the post. Crash tests at 62 miles per hour showed that a block of wood, but not metal, prevented a vehicle from catching on a post and coming to an abrupt halt in a crash.

Guardrail design had become geared towards holding a vehicle in its upright position while keeping it moving along the length of the guardrail, rather than slamming to a stop. Nor must the vehicle break through the guardrail; thus, the detail where lengths of W-beam are joined becomes important.The splice must be centered in the space between posts, where it is subject to less stress in a crash than if adjacent to a post. These specifications are incorporated in the Midwest Guardrail System (MGS) that became the recommended standard around 2009. The top of this guardrail stands at 27 inches.

Go forward to 2014 or so, and there’s yet another change. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials decided to switch their crash testing standards and opted for something called MASH (Manual for Assessing Safety Hardware). As reasons, they cite increasing size and height of vehicles and a better understanding of safety performance. The National Highway System has adopted these new standards nationwide. They are similar to MGS, but include another increase in guardrail height to 31 inches.

The ends of guardrails, known as end units, have also been re-engineered. The familiar, curved-out ends are being replaced with energy-absorbing end units that minimize the severity of impact when a vehicle crashes into the end of the guardrail. The “SKT” on the end unit stands for Sequentially Kinking Terminal, a design that bends or kinks the guardrail as the end unit is pushed along it by the force of collision, helping to bring the vehicle to a stop.

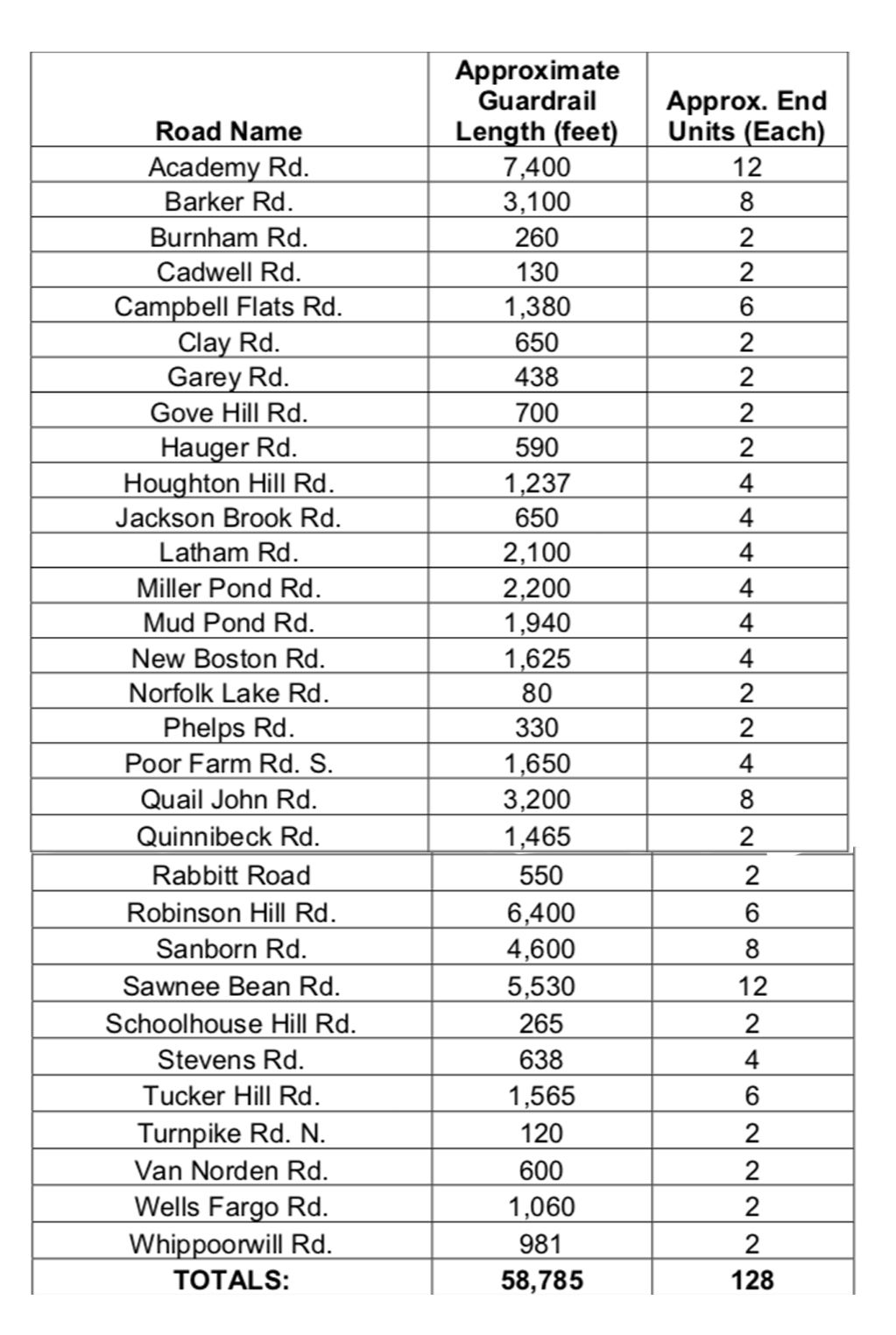

Thetford is finally catching up with the new standards, as evidenced by the taller guardrails on Route 132. And it doesn’t stop there. Stantec Engineering has surveyed all our guardrails and recommends that the town replace guardrails on the following roads to come into compliance with the MASH recommendation:

- Campbell Flat Rd, 300 ft; Ilsley Rd 385 ft; Latham Rd, 1,200 ft; Quail John Rd, 1,060 ft; Robinson Hill Rd, 1,056 ft; Tucker Hill Rd, 1,350 ft.

That’s a total of 5,351 feet or just over a mile of new guardrail and posts, plus 30 end units.

On Godfrey Rd, Mud Pond Rd and Old Stone Rd the height of the guardrail merely needs to be adjusted.

Academy Road, which boasts several stretches of aged guardrail, is listed as needing 7,400 ft of new guardrail, plus 12 end units, in the table below.

And, as part of Stantec’s 10-year road improvement plan for Thetford, the table recommends 58,785 ft of NEW guardrail with 128 end units, on various roads with unprotected drop-offs. Many of these roads are quaint, narrow, and wooded backroads, characteristic of a rural community. In their final comment, Stantec adds that “some of the roadways where additional guardrail is recommended may require roadway or shoulder widening for installation.” But are we ready to grace our informal and picturesque backroads with bright, shiny guard rails?