Vermont emissions could increase due to reported emissions reduction

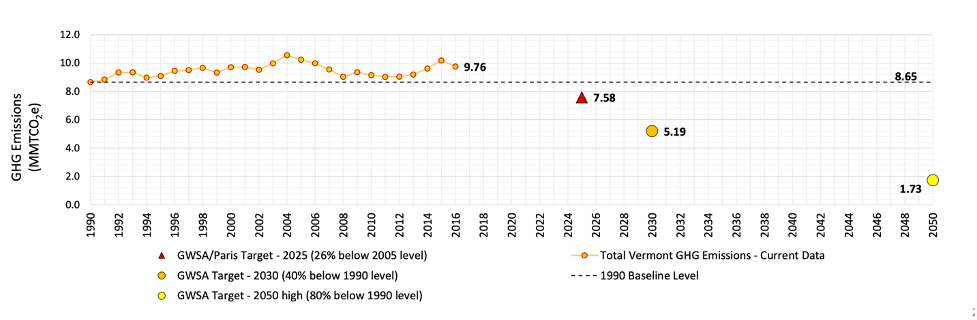

Apparently, Vermont is ahead of its 2050 emission reduction goals.

There will be a community meeting about Vermont’s Climate Action Plan on Saturday, September 11th at 10am at the Thetford Academy outdoor classroom. Scot Zens made the announcement on the Thetford listserv: “What can we do to ensure Vermont is the climate leader it wants and needs to be? Will our plan be effective enough to help avert runaway climate change? Who will this future benefit? Who might be left behind? The state needs to hear from us! Join 350VT and the VT Renews Coalition to learn more, share your thoughts, and join the call for a just and sustainable future that works for all Vermonters and the planet.“

Stuart Blood posted on the Thetford listserv a day later, “I've been following the proceedings of the Vermont Climate Council since early in the winter and, with the help of others who have paid close attention, I've compiled some background information, which may be helpful for others who want to help shape the direction of the state's Climate Action Plan.” A majority of the information in this article was sourced by Stuart.

State Representative and Thetford resident Tim Briglin, along with Rep. Sarah Copeland-Hanzas of Bradford and others around the state, was one of the co-sponsors of H.688, the Global Warming Solutions Act. The bill passed both Houses of the Vermont legislature in the 2020 session and was sent to Governor Scott’s desk for signature.

The bill replaced Vermont’s greenhouse gas reduction goals with requirements. For the first time, the State of Vermont could be sued if it failed to reach its own emission reduction targets. Those are: 25% below 2005 levels by 2025, 40% below 1990 levels by 2030, and 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

When Governor Scott vetoed the bill, the Vermont House voted 103-47 and the Vermont Senate voted 22-8 to override him, making H.688 law (Act 153). The new law established the Vermont Climate Council, with appointees from both the Governor and the legislature, and required the Council to adopt a Climate Action Plan by December 1st, 2021.

The Plan’s objective is to identify specific initiatives, programs, and strategies, including regulatory and legislative changes, that will allow the state to meet the emission reduction targets set in the new law. The Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) then has one year (until December 1st, 2022) to adopt rules and regulations consistent with the Plan.

A pre-existing law, 10 V.S.A. § 582(g), states that ANR:

... shall research and adopt by rule greenhouse gas accounting protocols that achieve transparent and accurate life cycle accounting of greenhouse gas emissions, including emissions of such gases from the use of fossil fuels and from renewable fuels such as biomass. On adoption, such protocols shall be the official protocols to be used by any agency or political subdivision of the State in accounting for greenhouse gas emissions.”

This means that the regulations adopted by ANR would apply broadly, including to the Town of Thetford (which is a political subdivision of the state) and our Regional Planning Commission.

The state has to determine how it is going to count emissions before it can develop a plan for reducing them. ANR made a presentation to the Council on December 21, 2020, entitled “Vermont’s Current Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Profile.” Included was a graph detailing where we are with emissions (up until 2016), and where we’re trying to go.

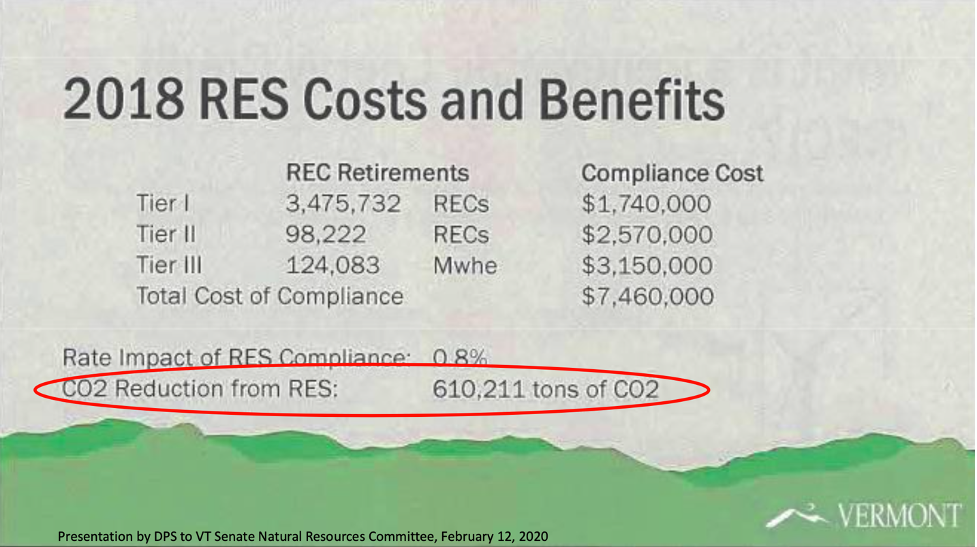

ANR then reported that from 2016-2018, Vermont saw an emissions reduction in the electricity generation and demand sector of 610,211 tons, from approximately 810,000 tons in 2016 to 190,000 in 2018. The accounted reduction put this sector ahead of its 2050 goals, leading ANR to conclude that emissions could actually increase in this sector and still be on target with the requirements of the Global Warming Solutions Act.

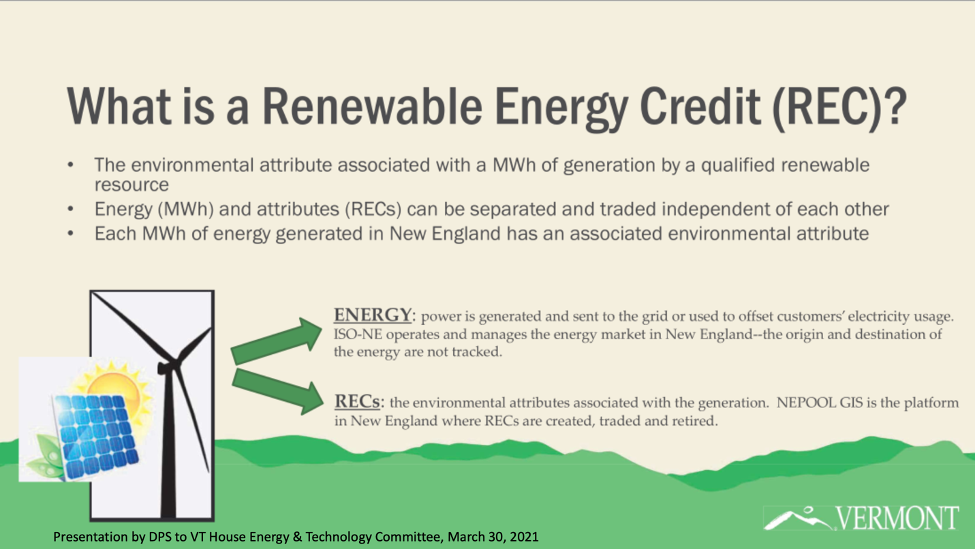

Like other New England states, Vermont uses Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) in its accounting of greenhouse gas emissions: “RECs are the tool used for accounting, tracking, and assigning ownership of renewal attributes.” The Department of Public Services says that RECs create a fungible commodity that can be traded, a uniform system for ensuring that there is no double counting, and allows for the transfer and tracking of ownership of renewable energy. “The ownership of a REC provides the right to claim the associated renewability.”

Understanding RECs is important in understanding how Vermont was able to report a reduction in its emissions by ~610,000 tons in just two years. RECs allow their owner to claim renewability by purchasing credits from a renewable source such as wind or solar, not necessarily by reducing their own emissions. The reduction could therefore be explained in one of two ways: an actual reduction in emissions, or an increase in the purchase of RECs.

In fact, of the ~610,000 ton reduction, roughly 74% can be accounted for by RECs purchased from Hydro-Quebec (HQ). Vermont is the only state in New England that gives HQ renewable energy status, and because no other state will take HQ energy as renewable, HQ’s RECs have a much lower market value. Under state law, “renewable” does not necessarily mean the source produced zero emissions, yet when purchased in Vermont, HQ’s RECs appear to reduce the state’s emissions. Roughly 30% of Vermont’s electricity comes from HQ.

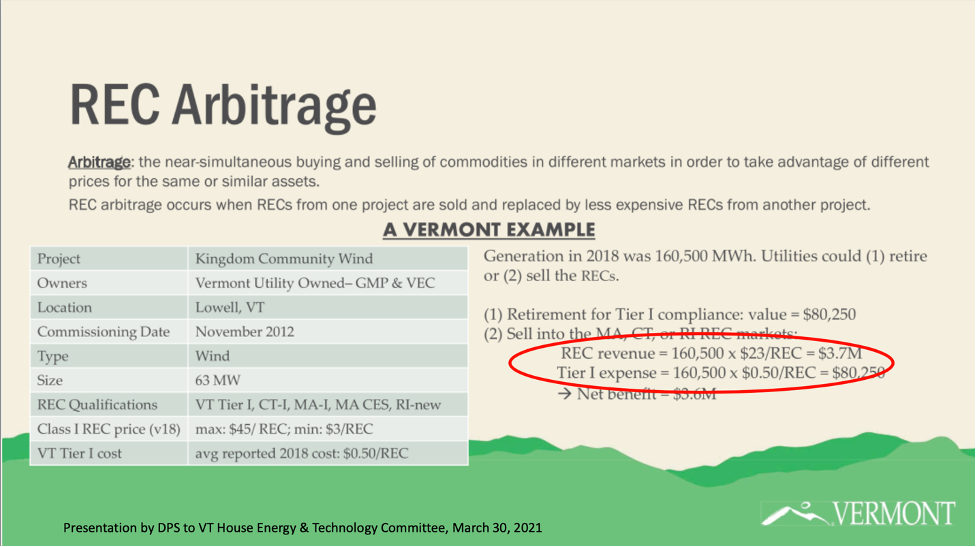

Green Mountain Power (GMP) – Thetford is in its service area – purchased 160,500MWh of RECs from HQ for $0.50 per MWh, which it used to claim renewability under Vermont’s energy standards. At the same time, it sold RECs to other New England states from energy generated at a wind farm in Lowell, VT for $23 per MWh, giving GMP a net profit of roughly $3.6 million. While other states are claiming renewability by using wind energy from Vermont, Vermont is claiming renewability by using hydropower from Quebec.

Renewability and zero emissions are not the same thing. Ben Gordesky writes in the Bennington Banner:

Massive hydropower projects can have a very large carbon and methane footprint. Unlike many of the smaller run-of-the-river hydro projects located in Vermont, Hydro Quebec’s dams store and release water when power is needed. They often flood and drain hundreds of square miles of forested land to store and release the water that generates electricity. As trees and vegetation that usually sequester carbon decompose under water, their stored carbon is released — some as CO2, but mostly as methane. Methane, although not as long lasting as CO2, is a far more potent greenhouse gas.

Due to Quebec’s relatively flat terrain, flooded areas often include low-lying wetlands and important soils as well. It is precisely this flat terrain that results in HQ having one of the lowest amounts of power produced per acre in the world. The soils in Quebec have been storing carbon since the last ice age.

An example is provided in an article by Brad Hager, an MIT earth sciences professor:

About a decade ago, Hydro-Quebec built dams to divert the Rupert River to the Eastmain hydro facility, flooding 175 square miles of virgin forest and wetlands. As a result, the first year after flooding, as much CO2 was released as would have been released by a coal-fired power plant generating the same amount of electricity!

Fortunately, the release of CO2 slows with time. Unfortunately, it never becomes insignificant. After five years, the total emissions from these Hydro-Quebec dams and natural gas power plants are about equal; after 10 years, the total release from hydro is “only” two-thirds that of natural gas. Extrapolating for a century, Quebec’s hydro is about half as dirty as gas – something of an improvement, but in no way “carbon free.”

Amanda Gokee writes in VTDigger that “HQ’s 550 dikes and dams have destroyed 3.8 million acres of native lands across Quebec.” Vermont, however, considers HQ’s carbon and methane emissions to be zero. Gokee quotes Collin Smythe, the author of the 2020 Vermont Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory and Forecast, as saying, “We do know that there are at least methane emissions that are due to hydroelectricity. We just don’t attempt to quantify those.”

HQ writes on their own website that “GHG emissions generated by creating reservoirs used to produce electricity are not considered when calculating our direct emission rate… Canada considers such emissions to be related to a land-use change.” While they link to a life-cycle assessment from their website, the page has been removed (Error 404 – Page Not Found).

Vermont has a legal obligation to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement, which requires that emissions accounting “shall promote environmental integrity, transparency, accuracy, completeness, comparability and consistency.” It is not a stretch to think that the Global Warming Solutions Act, under Vermont’s current regulations, could actually be resulting in increased emissions. This could be turned around if regulators accounted for the life-cycle cost of energy generation in Vermont’s emissions inventory, specifically that of large-scale hydro.