With skill and strategy, Thetford robotics teams qualify for world championship

Besides being an engaging challenge, robotics contests are a way to invest in the future.

In a gripping seven-hour elimination contest, robotics teams from Thetford Academy beat out formidable competition in the VT/NH Robotics State Championship to send five Thetford teams to the upcoming Robotics World Championship. In all, there were nine winning teams from Vermont and New Hampshire combined. Thetford Academy was the only robotics team from Vermont. The competition was fierce, coming from much larger and better-equipped schools ranging from Pinkerton Academy (ten times the size of TA) and Exeter High School (five times larger) to the small, technology-centric charter school Spark Academy.

The robot contest is a challenge on multiple fronts. It tests engineering design and computing skills, but also strategy and teamwork. Each year the Robotics Education and Competition Foundation (REC) poses a different problem for robots that enter the competitions, driving robot design and innovation. All schools purchase the same basic construction materials from REC, along with software downloads and rules for the year’s competition.

The 2022 challenge, “Tipping Point,” was a game where robots scored points by placing 4-inch rings into cup-like “goals” or, for more points, threading them onto tall rods rising from the center of each goal. They could also physically move some of the goals into their home zones for more points, and if they ended the game by elevating themselves, or better still, a pair of goals, on a hinged, balanced platform, they scored yet more points. It was a timed event lasting two minutes, starting with a 15-second autonomous period and then driven by remote control.

Adding more complexity, robots didn’t compete singly. They had to cooperate in randomly allocated pairs or “alliances” pitched against another pair. To win, they had to develop a cooperative strategy.

The qualification matches alone involved 37 robots and 74 contests because robots swapped pairs. It took five hours. Thetford teams survived some fierce competition to enter the next round of eliminations. In the semi-finals they even found themselves vying against each other. Two Thetford teams, Tate Whiteberg’s “Turbo Encabulator” and Caleb Crossett’s “Waluigi,” made it into the top four, along with two teams from Pinkerton Academy. Realizing that if the two Pinkerton robots teamed up they might be unbeatable, Tate strategically partnered with one of them. The remaining Pinkerton team chose to partner with a lower-ranked Thetford robot — the “Beefcake” of Marshall Melancon, Isaiah Kol, and Michael Frenandez — because their robots complemented each other. Meanwhile Caleb partnered his Waluigi with “Skunkworks” from Thetford juniors Eldon Crossett and Avery Crandall.

Tate’s Turbo Encabulaor and its Pinkerton partner emerged victorious to win the VT/NH State Championships.

The above action involved high school teams. In addition, the ROC had a category for middle schools, and the only one to send a middle school team was Thetford Academy. Thus seventh-graders Rowan Moody A’ness, Tristan Woodward, and Paul Hesser earned that award, plus a spot to compete in the World Championship.

In parallel to the playoffs, the ROC ran a separate Skills event. Individual robots demonstrated their abilities, operating completely autonomously for 60 seconds and under remote control for another 60 seconds. This event was dominated by Tate’s Turbo Encabulator, with 20% more points than the competition. Two other Thetford teams (Aden Perry with Connor Cutter-Walker, and “String Theory'' from Duncan MacPhee) earned the 5th and 6th highest Skills scores. At the end of the day, five of the six Thetford teams qualified one way or another to go on to the World Championship.

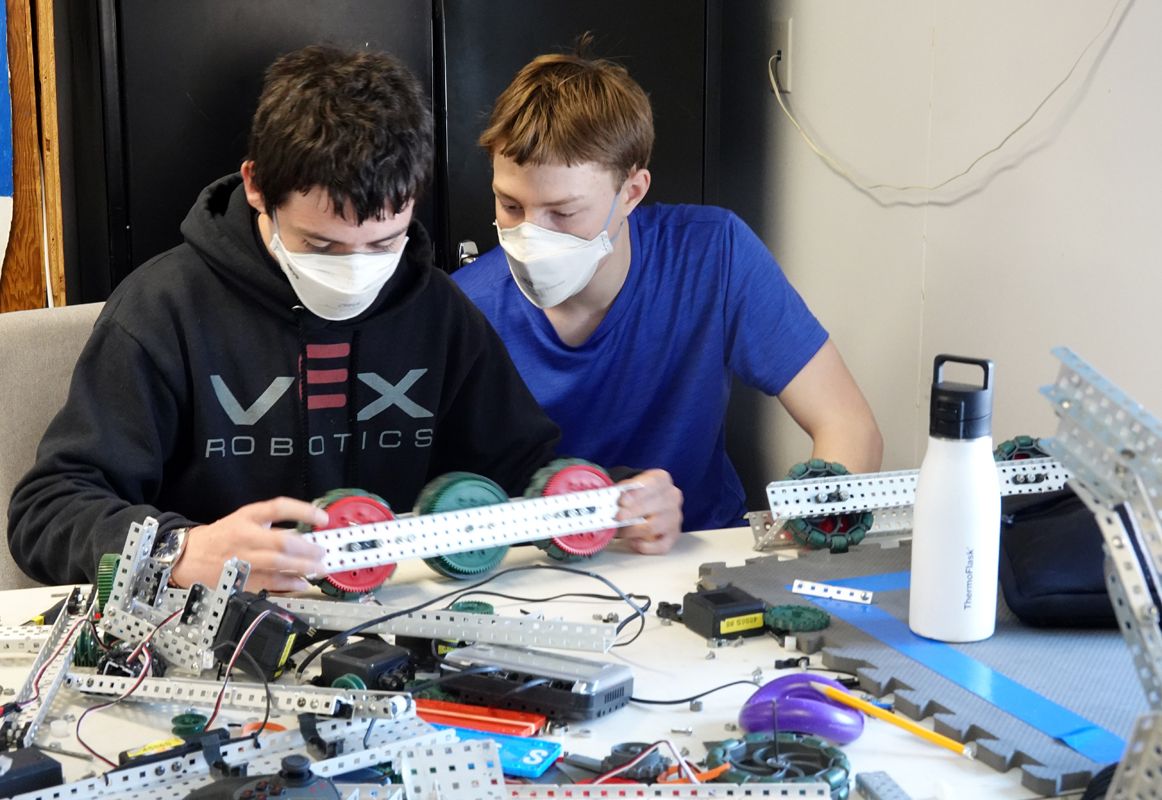

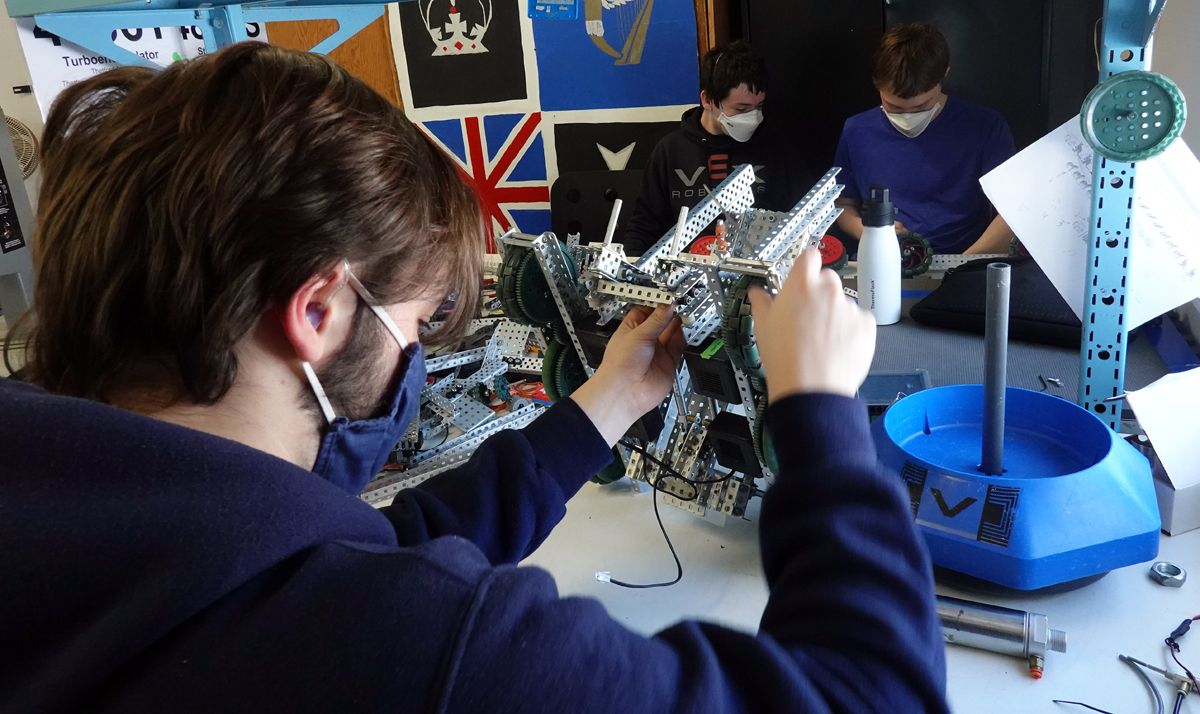

Back in the Robot Room at Thetford Academy (TA), the winners didn’t rest on their laurels. They tore apart their robots to refine, rebuild, and re-test in preparation for the World Championships. There is no rule to say the robot from the State Championships is the one that goes on to the World event. The real goal of these competitions is to spur innovation and improve problem-solving skills.

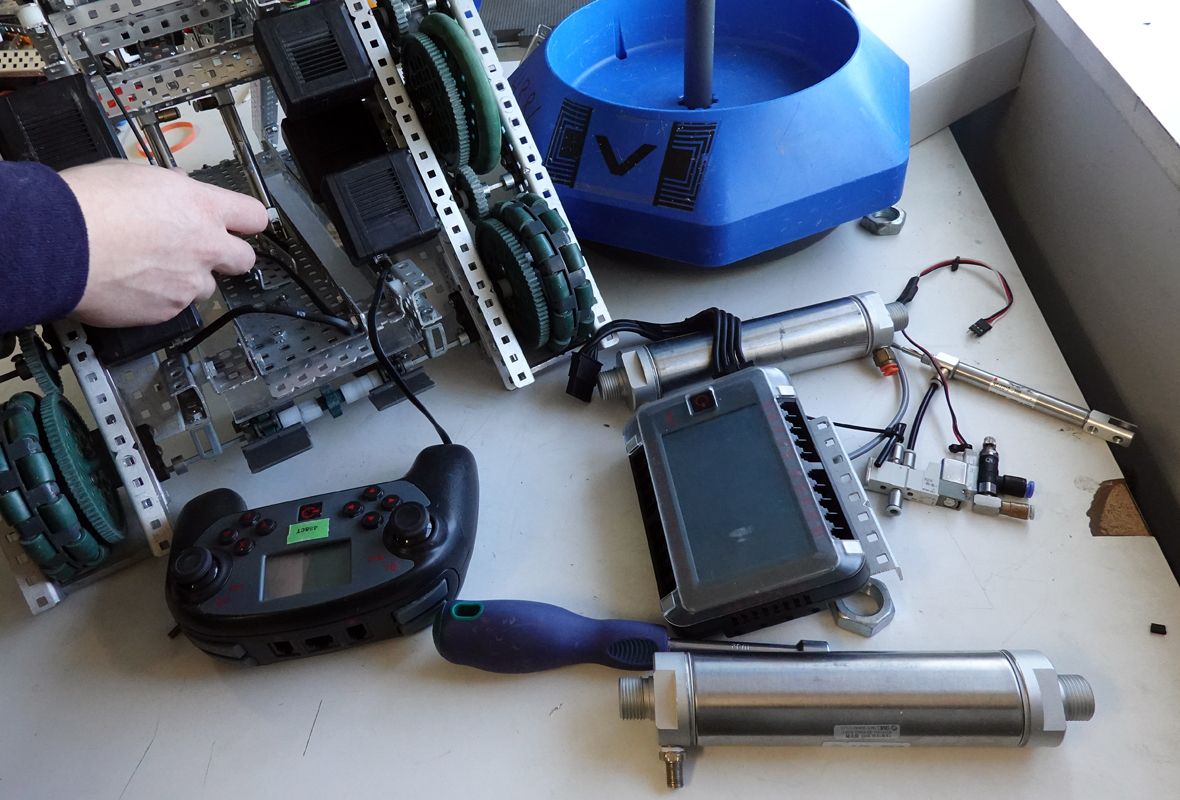

Robot designs are driven by the game they must play. In a previous year, the game involved throwing balls to hit flags and produced a crop of very different robots. Tate is redesigning because his winning robot can’t do some of the tasks required for the World Championships. He explained some general competition guidelines. Robots cannot exceed 18 inches on a side, thus some are cube-like. The robot he was working on had six motors to move in different directions. Robots may only extend themselves up to 36 inches by way of pneumatic attachments powered by two compressed air tanks. This allows the robots to pick up the rings to place on tall rods or move goals onto the balancing platform. The students send radio commands to their robot’s “brain” by way of a hand-held control module.

Tate’s favorite part of the contest is the autonomous challenge. While every team must learn the C++ computer language, programming a robot to perform autonomous tasks is a “huge deal.” Rival teams and their coaches were so impressed by the autonomy of Tate’s Turbo Encabulator that they asked him for lessons. Obligingly, Tate will teach a course, making sure to pass his knowledge on to other TA teams since, as a senior, this is his last year at the Academy.

Seventh-graders Rowan and Paul were also rebuilding. When asked if they were nervous at the State Championship, they replied that it was “very exciting.” They too had to write computer programs. Rowan added that they had learned some “regular coding,” but writing code to perform functions was “weirder than he thought.” It was a good challenge and fun when it worked. The best part was meeting people at the State Championships. Five minutes before competing, nobody was ready, everyone was fixing things at the last minute.

One wonders how Thetford Academy, a school of 339 students, produced such phenomenal robotic talent. Leif LaWhite, Tate’s father, thinks that one key to success was allowing a lot of time — 7 to 9 hours during the week plus more on weekends. TA robotics teams do not receive much in the way of guidance from teachers. They are self-motivated learners, finding things online to try out, build, and refine. Leif’s main role was to remind them of the rules of the competition— “how you win and how you lose.” And having a dedicated Robotics Room (formerly the Chorus Mansion) was a major contribution. Here, each team could have their own workbench, their own tools, and their own level of creative mess.

The next robot tournament will be the World Championship in Dallas, Texas, where TA students will mingle with teams from far-off places like Japan, Singapore, Europe, South America and Australia. But win or otherwise, the real gains are in developing skills in engineering design, fluency in computer programming, inquiry-based learning, teamwork, and problem-solving. Some predict that in the next decade, jobs requiring science and technology skills will grow by 8%, compared with only 3.3% for all other jobs. Besides being an engaging challenge, robotics contests are a way to invest in the future.