Wildlife Road Crossing Study: life in a fractured landscape

The ability to move is increasingly important as climate change disrupts animal habitats.

On November 19, the Thetford Conservation Commission hosted wildlife biologist Jesse Mohr who gave a presentation of his two-year study detailing wildlife road crossings in Thetford. One may ask, why is this a topic worthy of such attention?

It's an under-appreciated fact that the rural lifestyle many of us enjoy is dependent on a lot of driving. We've gone from the self-sufficient villages of old to traveling miles to reach centers of commerce and employment. Vermont is now criss-crossed by over 15,000 miles of roads, about 8,500 miles of them unpaved.

However, people are not the only ones who travel back and forth. From time immemorial, animals have been moving across the landscape guided by resources essential to their survival.

These journeys may be local or long-distance. Deer, for instance, move daily between their bedding areas and places where they forage. Amphibians like frogs and salamanders make yearly local journeys to and from their breeding pools or wetlands. Carnivores have an innate need to wander widely. This can be seasonal and cyclical, going from place to place for hunting and breeding. Some also undergo once-in-a-lifetime, long distance dispersals when they leave their mother's territory to establish themselves permanently, tens or hundreds of miles away. Animal movement also serves the important function of genetic mixing between different populations.

In all of these relocations, animals must encounter roads. To humans, crossing a road may be a minor inconvenience, but to animals roads present serious barriers. Most animals instinctively avoid roads and road edges*. Traffic noise and volume of vehicles are major deterrents which only worsen with high-speed roads. Animals that attempt to cross may be injured or killed, and in the long term this can result in local populations – for instance of turtles – becoming extinct.

Because of crossing reluctance, the division of forest into parcels bounded by roads is causing fragmentation of habitat into smaller and smaller areas that no longer supply all the resources needed for survival. Habitat fragmentation also results in genetic isolation and inbreeding, making animals less resilient. The effects of habitat fragmentation don't stop with animals. It also affects the ability of plants to disperse seeds, cross-pollinate, and remain genetically fit.

On a grand scale, models based on present trends suggest that roughly half of the world's animal species are relocating because of climate change. However, constraints on dispersal, including habitat fragmentation, mean that many will be unable to reach suitable new terrain and are doomed to disappear, probably by 2070.

Understanding the location of road crossing points is a critical first step to maintaining the biodiversity we have in Vermont. Jesse Mohr's examinations of crossings in Thetford, which has a significant amount of forest, are a valuable contribution that goes beyond the largely computer-generated models from the State by providing on-the-ground, real observations.

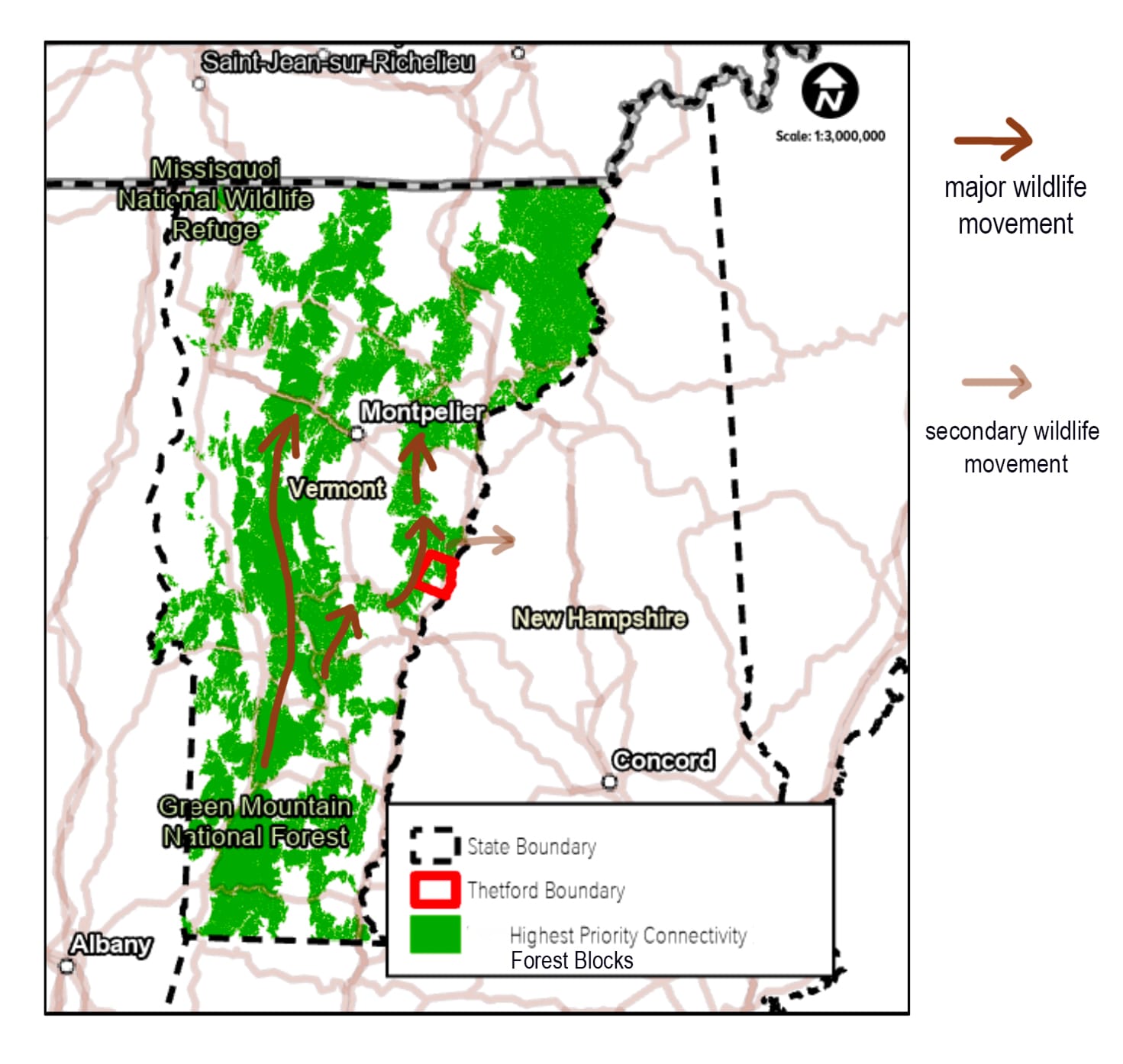

In his report, Jesse draws a distinction between wildlife road crossings that allow local movement and those that are regional. The latter "are part of a broader regional network of connected lands that support ecological connectivity and climate resiliency across the Upper Valley, VT and the greater Northeast region." Thetford is home to such crossings because the town sits on a north-south belt of Highest Priority Connectivity Forest running parallel to Vermont's main north-south connection – the spine of the Green Mountains. In addition, the town is located in a second belt of east-west connections, albeit interspersed with development, between the Green Mountains and Worcester Range and the White Mountains in New Hampshire.

In general, wildlife prefer to cross where there is good forest cover on both sides of the road and the terrain is flat to gently sloping. Steep roadside banks and rocky ground, such as rip-rap to prevent erosion, are deterrents.

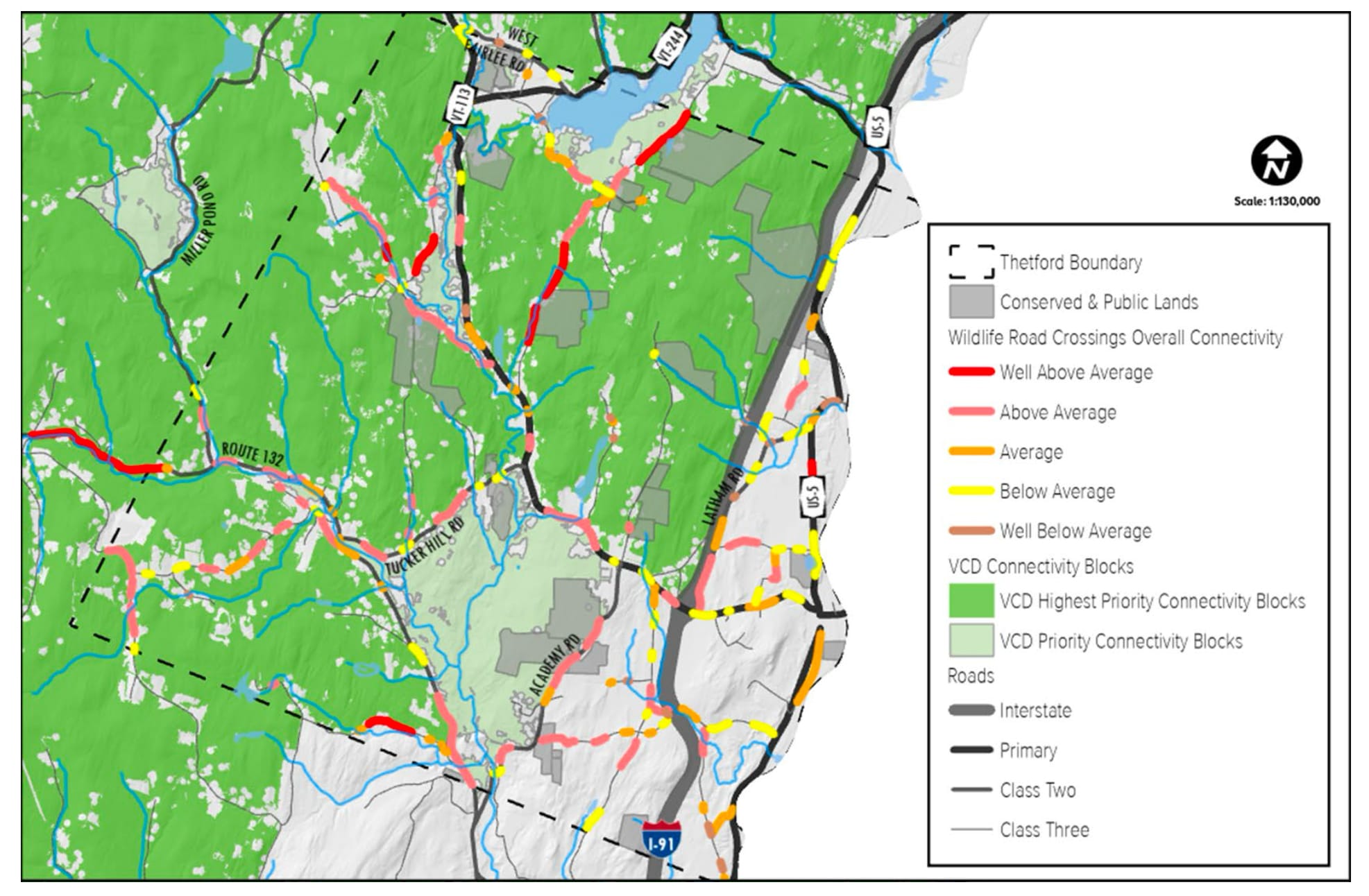

Jesse identified 131 wildlife crossings in active use, with a cumulative length of almost 26 miles of roads. Forty-seven sites, totaling 15.1 miles, were ranked as being of greater importance. Active use was verified in winter by observing animal tracks in snow on both sides of the road. While animals do cross Interstate 91, it was not studied for obvious safety reasons. Most locations were used by deer – by far the most common species, plus fox and coyote. Far-ranging carnivores (bobcat, fisher, otter) and bear (a far-ranging omnivore) were recorded at only 28 crossings that encompassed 8.2 miles. Moose, another species with a large range, were not recorded at all.

Bridges and culverts are used by wildlife for crossing under roads. However, in Thetford that use is limited to only six structures out of the 78 that have sufficient headroom for animals to pass. Only 13 structures offered any dry terrain for animals to walk on, and of those many were too close to houses or lacked sufficient forest cover to encourage their use. When water under a bridge or in a culvert is frozen, animals will walk on the ice to pass under roads, but due to our warming winters, water that would have been frozen remained open at the time of study.

The only structure that allowed all animals, big or small, to pass comfortably was the Rt 132 bridge over the Ompompanoosuc West Branch. A generous section of dry riverbank passes under the bridge, and there is ample headroom.

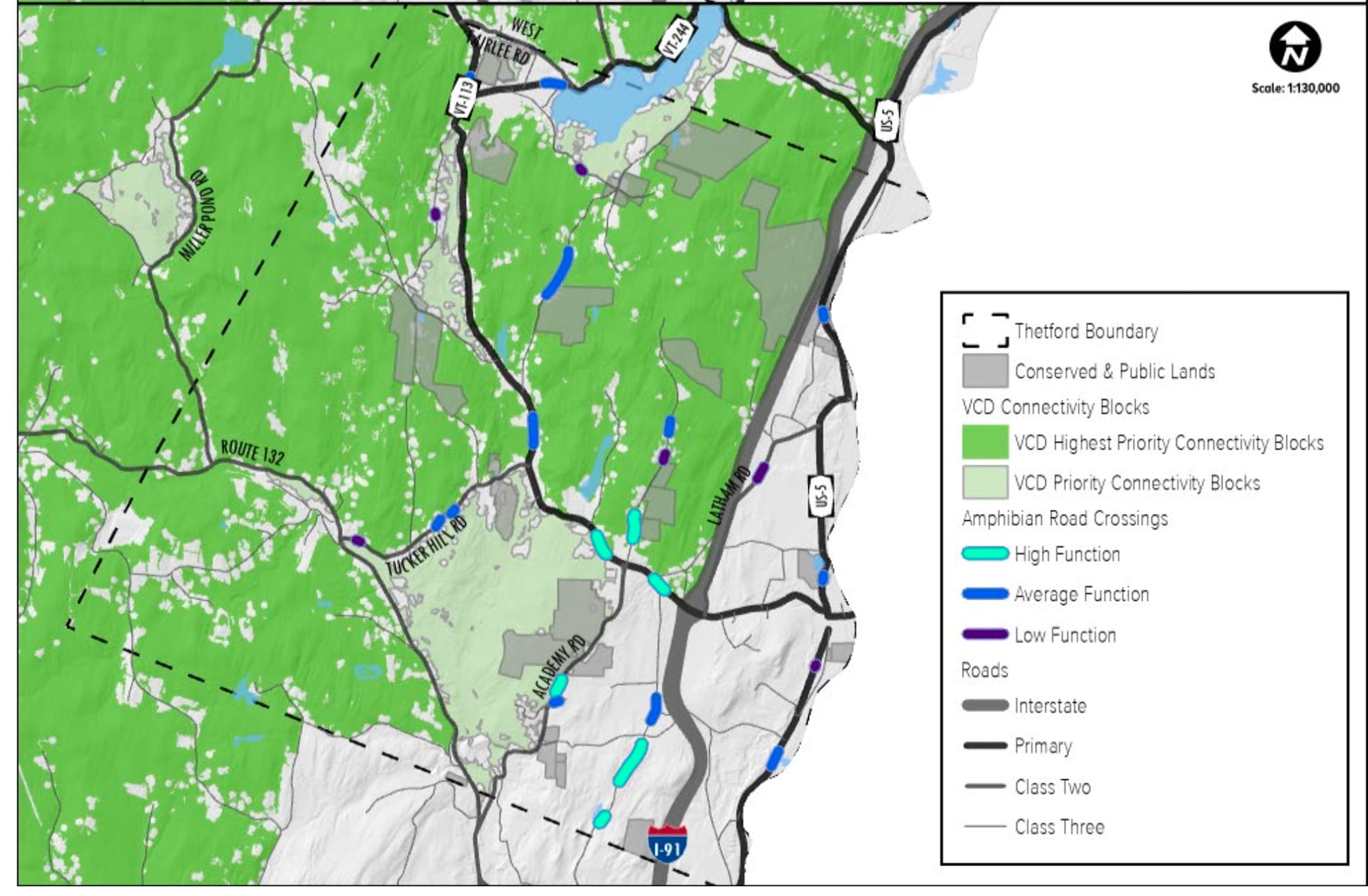

Another class of wildlife – amphibians and their crossings – were studied by the Thetford Conservation Commission and citizen volunteers as well as by Jesse. Out of 48 potential amphibian crossing sites, 24 were observed in use, though sites were not monitored equally due to weather conditions, survey timing, volunteer availability, etc. Later-migrating species were under-represented in these surveys. Two amphibian species listed in the Vermont Wildlife Action Plan (a federal initiative) as Species of Greatest Conservation Need were documented, the spotted salamander and the far less common four-toed salamander. The latter is a first for Thetford.

All this data was summarized into a series of maps.

Five Corners Road and part of Rt 132 on the Thetford-Strafford line emerged as regionally important crossings. Five Corners Road cuts between two Highest Priority Connectivity Forest blocks, and the road has few house clearings and several open wetlands. There are, in fact, four active wildlife crossings in this stretch of road. Two adjacent high-ranking ones are separated by a house. There is also an amphibian crossing.

Another regionally important crossing is located on Route 132 approaching and going into Strafford. The road here is flanked by two Highest Priority Connectivity Forest Blocks that are large and regionally important. There is also a high-ranking crossing area on Rt 132 that includes the beginning of Gove Hill Rd, both very close to the bridge over the Ompompanoosuc that allows all species to cross.

A number of regionally important "above average" wildlife crossings also exist, e.g on Miller Pond Road, Gove Hill Road, New Boston Road, etc., and there are numerous locally important crossings that should not be ignored.

It is critically important to safeguard the function of these crossings by encouraging landowners to maintain roadside forest cover and, where it applies, vegetated riverbank and wetland buffers. Voluntary land conservation is the best tool, though not everyone wants to take this route. Where a road section encompasses several crossings, at least one should be protected. For marginal crossings, the restoration of roadside vegetation should be considered.

Regionally important crossings can link large forest blocks, but we must not forget that smaller linkages between smaller blocks serve as stepping stones for animal movement. The ability to move is increasingly important as climate change disrupts animal habitats, causes mismatches between availability of food sources and breeding cycles, and encourages new diseases. The least we can do is ensure that routes enabling animals to migrate northward, or to higher, cooler elevations, remain open.

*An exception to road avoidance occurs when deer and moose are attracted to lick pools of snowmelt and road salt in the winter, a season when they may suffer from mineral deficiency.