Village water part 2; East Thetford‘s struggle

The fewer the number of users, the more each one has to pay.

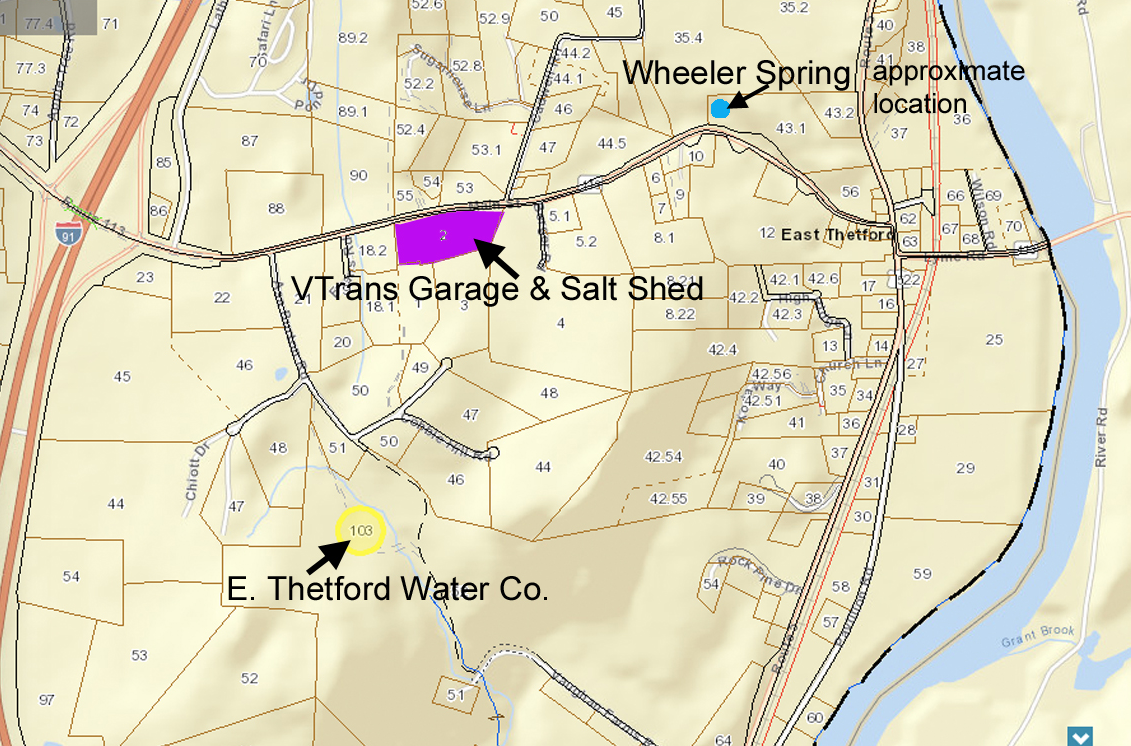

Back in 1961, a communal water system seemed like a sensible approach for East Thetford. There was a spring near the bottom of Rt 113 as it climbs up from the village — the Wheeler spring — that delivered good, clean water. Over 40 households abandoned their individual wells, some that delivered water of inferior quality, instead filling storage cisterns in their basements with spring water piped to the home. This system ran without notable incident until 1988, when the Wheeler spring was found to be contaminated with road salt. Was it a coincidence that the State salt shed was located uphill from the Wheeler Spring? The state agreed to drill a new well at no cost to the water company, while never acknowledging any direct responsibility for the salt. The new well, 400 ft deep, was situated high on a hill above Vaughan Farms, feeding into a reservoir at the upper end of the new pipeline that runs alongside Asa Burton Road to supply water to East Thetford residents.

lThe new arrangement seemed perfect. In the beginning, the well delivered 60 gallons per minute, more than enough to keep the reservoir full. However, around 2009 the well’s capacity began to dwindle. Hydro-fracking in 2015, with the hope of opening up more water-bearing seams, made no difference. The water diminished to 3 or 4 gallons per hour.

One day in early 2019 there was just no water. East Thetford businesses were suddenly shuttered. Chris Hebb, the consulting engineer for village water companies across Thetford, dug through the snow to re-open the flow from Wheeler spring on an emergency basis. He arranged to fill the reservoir from the drilled well with water brought in by tanker truck from Stockbridge, Vermont. Residents switched to bottled water for drinking.

The solution? Drill a second well. This was accomplished in 2020, thanks to Vaughan Farms, who allowed the use of their land. The new well is 840 ft deep — the bottom is actually lower than the bottom of the Connecticut River — and it delivers over 70 gallons per minute. So far, so good, but then the bureaucracy begins.

Private water companies operate under the rules of the Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division of the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The administrator from the state argued that the pump from well to reservoir must deliver 25 gallons per minute, based on “estimated consumption.” However, by now, the Water Company had shrunk to only 35 households, as some disgruntled customers had reverted to private wells. Chip Hobson, who was Water Company treasurer for many years, pointed out that a pump providing 4 gallons per minute (gpm) around the clock was all that was needed to keep the 15,000 gallon reservoir full. An expensive 25 gpm pump would cycle on and off — a good way to burn it out. The response from the state was that “deviation from the guidelines” placed the responsibility on the state administrator if things were to go wrong. The Water Company was thus granted a permit for an 18 gpm pump, with the proviso that it must be replaced with a 25 gpm unit “in response to growth.” Even the 10 gpm compromise that Chip offered deviated too far from the DEC’s standards.

In fact, when the first well ran dry, the state recommended that the Water Company commission a $15,000 engineering study to evaluate the entire system. The evaluation included a “primary social study” of the potential for growth and development of the village. It concluded that there was so little developable property that growth would be insignificant. East Thetford is geographically and economically restricted.

The Water Company was also slapped with a $2,700 fine for running the pipe from the new well to the pump house through a wetland buffer, without a permit. The permit would have been a formality, but the application was sent after the fact. The state preferred a route for the pipe that avoided the wetland and would have added the extra expense and time of blasting through ledge.

The water in the new well contains low levels of manganese and iron, common components of our bedrock, in amounts that the EPA classifies as “an aesthetic issue.” The ultimate way to remove them is to install a costly water filtration system at the pump house. The interim approach is to add small amounts of phosphate that keep the minerals from depositing and staining plumbing fixtures. Drinking water regulations require the Water Company to inform its customers annually of the levels of minerals. Some users are now afraid to drink the water, in spite of the EPA’s assurances.

Chip has been trying to iron out the finances of the Water Company for twelve years. The new well was funded by an interest-free loan of $135,000 through the VT Economic Development Agency. Because manganese and iron are common in well water, the state left the loan “open” to accommodate additional borrowing for a water treatment system. This would drive the loan up to $350,000, but once everything is installed and meets approval, EPA funds would cover 75% of the costs. The remainder would be paid by the Water Company over 20 years, interest-free.

An application to finance the filtration system was submitted two years ago, but until recently there had been no action from the state, no replies to emails, even though the Water Company paid the wetland violation fine to remain eligible for the program. Rumor has it that the DEC water administration is stumbling and suffers from a staff shortage. A state Water administrator recently replied to Chip Hobson, explaining that they were “swamped” but were finally working on the “environmental determination” regarding the wetland. But after all this, several East Thetford businesses and landlords have called it quits and gone back to private wells. And who can blame them? Some, like a daycare and a dentist, cannot operate without reliable water. And, with its small number of customers, the Water Company fees have gone up to $800 a year per connection. A landlord with a four-unit rental must pay $3,200 for water alone.

The fewer the number of users, the more each one has to pay. And those who remain on the Water Company system include residents living on fixed incomes, who have no other water options.