“Turf Wars” — No Mow May or a nuanced approach?

At this point, nature needs all the help it can get.

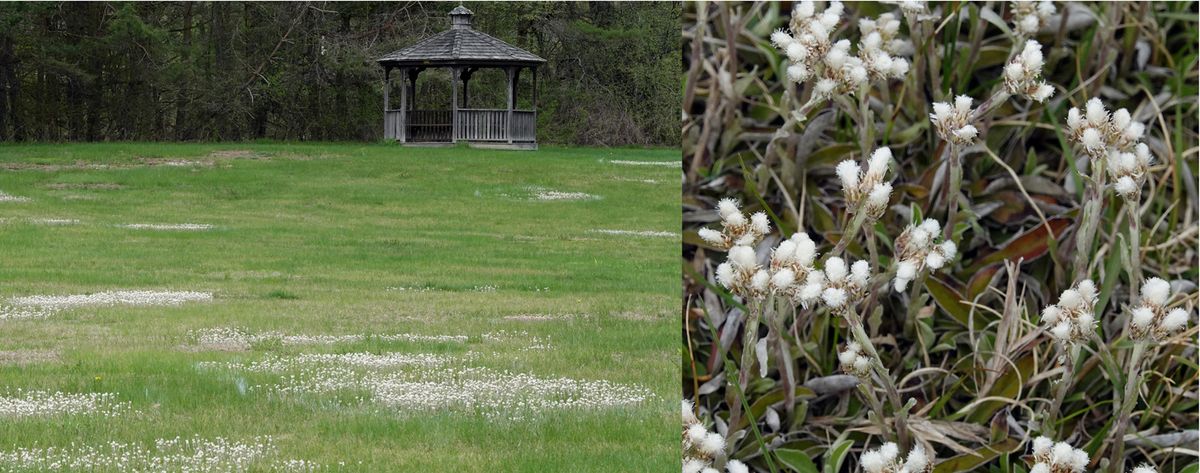

On May 1st, after hearing arguments from the Joint Thetford Energy Committee (JTEC), the selectboard approved the motion “To mow (the Town lands, excluding the ball fields) no more frequently than every two weeks for this season, and not mow the Pussytoe plants on the Thetford Center Green for the month of May. The selectboard will reevaluate for a future decision.”

The JTEC’s arguments could be summarized as follows: Turf grass, at over 40 million acres in the US, is the nation’s largest irrigated crop, according to the US Department of Energy. That is three times more than corn, because most of the 80-90 million acres of corn in the US are not irrigated.

To maintain this turf, mowers consume 1.2 billion gallons of petroleum fuel per year or 1% of the nation’s total gas/diesel consumption. “A single commercial lawnmower can annually use as much gasoline or diesel fuel as a commercial work truck.” Thus the JTEC urged the town, as well as private lawn-owners, to reduce their carbon footprint and provide early season forage for pollinators by taking up the No Mow May initiative. Beyond not mowing in May, the ultimate “gold standard” would be to reduce the area kept as lawns by 50%.

The town’s mowing contractor was aware of the interest in No Mow May through discussion with the town manager. However, he was not impressed with the selectboard’s decision, even though it did allow at least one May mowing.

“I hear that this is coming from a place of saving energy usage and saving pollinators. The move to (mow) every other week does not accomplish that goal. When we allow the grass to get higher it requires double cutting — mowing the whole lawn twice, and even more if I need to bag the cut grass as well. This severely impacts the hours for me to accomplish my end of the contract. … I take pride in the work that I do. I fear that delayed mowing, thatching and clumps of grass will look very different from the work I have done for you over the past 5 years. Imagine on day 14 that we get a stretch of rain – the grass will continue to grow and when we can finally mow it, it will be a mess. It is impossible to predict the growing season….”

The selectboard favored the two-week mowing, rather than all-out No Mow May, partly from reading a research study funded by the National Science Foundation. Researchers examined the effects of less-frequent mowing on 16 suburban lawns in western Massachusetts. They compared lawns mown at 1-, 2-, or 3-week intervals and noted that although lawns mowed every 3 weeks had the most flowers along with “significantly taller grass,” lawns mowed every two weeks had the highest bee abundance. They attributed that to easier access to flowers in shorter grass.

The town Conservation Commission had a more muted response to No Mow May. The above study noted that “spontaneous lawn flowers” included dandelions and white clover, both of which are non-native. Dandelions in particular bloom early and offer a source of nutrition to wild bees in the critical period when queen bees emerge. Unlike domestic honeybees (exotic non-natives), wild bees don’t have colonies that persist from year to year. Only the queen bees overwinter. In spring they work diligently to start a nest, lay eggs, and provide food to nourish the first brood of worker bees. If the colony doesn’t get off to a good start with top-quality nutrition, it will never be vigorous. Bee larvae must have protein to develop, and this comes from flower pollen. But dandelion pollen lacks some of the essential amino acids that are required. Research has shown that a diet of pure dandelion pollen will hinder larval development in mason bees, prevent larval growth in honey bees, and cause 100% larval rejection in bumble bees.

Dandelion pollen also inhibits seed formation in native wildflowers if it gets dusted onto those flowers by visiting bees. In fact, dandelions may owe their worldwide distribution as much to their inhibitory effects on other plants, an effect known as allelopathy that includes nasty compounds exuded by their roots, as to their flying seeds.

So what’s a homeowner to do? Not mowing for a whole month and then suddenly denuding the ground may not be wholly beneficial. It leaves pollinators with nothing, while probably killing the majority of insects that had moved into the unmown vegetation.

We could take some tips from research performed by citizen scientists (and analyzed by professionals) who studied insect habitat in urban lawns that were managed as “butterfly meadows'' with a reduced mowing schedule as follows: “(1) maximum of three mowings per year; (2) at each mowing, leave about 30% of the lawn uncut, while rotating this un-mown part each time; (3) no mulch; (4) mandatory removal of the mown grass.” They made five data collections (May-August) from these lawns and found an insect biomass (including pollinators) of 1.26-4.51, plus 136 plant species in bloom. By comparison the same visits to intensively mown lawns found an insect biomass of 0.01-0.33.

This approach, or a variation thereof, could work for homeowners who wish to keep their lawn as open space while utilizing its potential for plant, pollinator, and insect diversity. But obviously the town green wouldn’t be the same recreational space if it were maintained this way. For early season pollinator food, be especially careful to spare Pussytoes, violets, Robin’s plantain, alpine strawberry, and Prunella (aka the medicinal herb self-heal).

The goal of a 50% reduction in lawns is still a gold standard in terms of saving energy, regenerating biodiversity, restoring insects, and providing for pollinators, while keeping some lawn. We are in an era where insect numbers are declining worldwide. The majority of birds, irrespective of their adult diet, rely on insects as THE protein-rich food for their nestlings. We’re already seeing a reduction in numbers of specialist insect-eating birds. At this point, nature needs all the help it can get.

Photo credit: Li Shen