Race against extinction - the Homegrown National Park

Cedar Circle recently received a grant to convert a portion of the organic cut flower garden to native perennial plants, develop educational materials, and host workshops over the next two years.

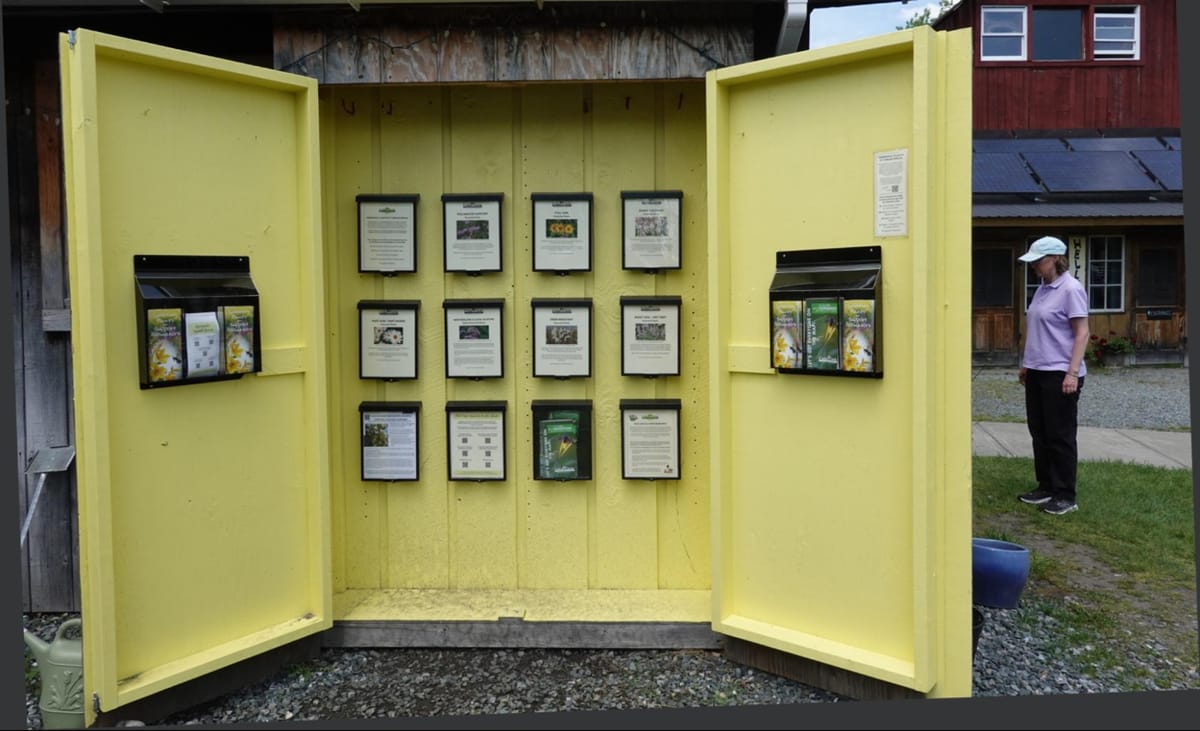

Visitors to the Cedar Circle Farmstand on Pavillion Road in East Thetford may notice a newly-painted, sunshine-yellow kiosk on the side of the building. It offers a selection of informative leaflets on garden and landscaping plants. Specifically, one leaflet explains that "We have shifted our perennial plants offerings to focus only on species we believe will have positive ecological impacts on our local landscape." Another explains how plantings that support pollinator insects help to "build resilience into our local ecosystems and regional landscape."

Perhaps the most important leaflet, one that sets the context for the rest, is titled "HOMEGROWN National Park." This concept originated from the writings of wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy, author of several books including New York Times bestseller Nature's Best Hope.

To summarize some of Tallamy’s key points behind the HomeGrown National Park initiative: Humans have converted 54% of the area of the lower 48 states into an array of cities, suburbs, roads, shopping centers, and other infrastructure, with isolated habitat fragments scattered in between. The surface occupied just by paved roads is four times the area of New Jersey. A further 41% of the U.S. is under various forms of agriculture. In other words, 95% of the natural world has been made unnatural, with a dearth of native plants and insects.

Why does this matter? All animals feed on plants or on creatures that have fed on plants. That's how sustenance is passed through the food web. Insects are by far the most important group for passing the energy in plants along to other animals. They do that by being eaten in vast amounts. Globally, birds are estimated to eat 400 to 500 million metric tons of insects per year .Thus, insects are vital components of healthy ecosystems and biodiversity. Because so many animals depend on insects for food (96% of all terrestrial birds, also spiders, reptiles, amphibians and rodents), the loss of insects from a food web spells its extinction.

Here's the catch: All plants protect their leaves with a cocktail of noxious chemicals that is unique to that plant species. With few exceptions, only insect species that have evolved alongside a particular plant lineage have adapted to digest those leaves, because they have evolutionary tolerance to the chemicals. When insects in Vermont encounter plants that evolved on another continent, it is likely those insects will be unable to eat them.

Extensive scientific research reveals that the area of land required to sustain biodiversity is roughly equal to the area that generated it in the first place. The consequence of this simple relationship is devastating. Since we have overrun 95% of our natural areas, we can expect that 95% of the species that once lived there will become extinct unless we learn how to foster biodiversity within our living, working, and agricultural footprint. That means we must share our spaces with the native plants and insects that support the rest of life.

However, we have designed landscapes with no thought to our local ecosystems, instead favoring ornamental plants from Asia, Europe, and South America over those that have evolved right here. But non-native ornamentals support only 3.4% of the animal diversity supported by native ornamentals. Some 40 million acres (over 62,500 square miles) is planted in lawns of non-native grasses, and an area as big as New England is mowed each weekend.

Why care? The ecosystems that underpin the earth’s ability to support humanity are made up of the native plants and animals around us. Plants are the generators of oxygen and clean water, they create topsoil from rock, and they buffer us against droughts and floods. It is insect decomposers that drive the earth's nutrient cycles and sustain each new generation of plants and animals. It is pollination by insects that allows the continued existence of 80% of all plants and 90% of all flowering plants. Birds and other animals feed on insects, thereby controlling their numbers, and also disperse the seeds of plants.

While scientists debate the extent of decrease in insects populations, an overview of 73 studies estimated a 2.5% decrease per year in insect biomass in the US and Western Europe. It cautioned that this trend could point to the extinction of 40% of the world's insect species over the next few decades. A less scientific, but nevertheless telling, local measure is the “windshield test” — car windshields covered in dead insects after a short drive in the country. While this was a common problem in the 20th century, 21st century drivers can go a whole summer without noticing it.

Without too much effort we can do better than continue to degrade biodiversity. As the Cedar Circle leaflets suggest, everyone who owns land has a perfect opportunity to enhance local ecosystems by choosing landscape plants that have ecological function, including trees and shrubs. And if we convert an equivalent of half our collective lawn space to native plantings we will have restored 20 million acres of biodiversity — a Homegrown National Park!

We can thank Stacy Cooper, a recent addition to the Thetford Conservation Commission, for this critically important local initiative. When Stacy started working at Cedar Circle, which is an educational foundation as well as a farm, she noticed that while there was an interest in native plantings, additional energy would help align the plant departments with the educational mission. She soon convinced the farm to change their perennial offerings to encompass more native species. And the ability to support pollinator insects is foremost in the selection of perennials that are not native.

Stacy did not work alone in assembling the handouts and invigorating Cedar Circle's educational aspect. She drew upon the resources and mentorship of Thetford residents Scott Stokoe and Anne Fayen, who helped with research, drafting and editing. To build educational and plant offerings, there is also ongoing coordination and cooperation with other entities, notably the Intervale Conservation Nursery and the Vermont Center for Ecostudies that is currently engaged in a community science project on pollinator-to-plant interactions. The cooperative extensions of University of New Hampshire and University of Vermont are also partners, visiting the farm last year to perform pollinator counts and other studies, which will be a useful comparison to this year's research. Another resource is the Wild Garden Alliance, a project of pollinator biologist Alicia Houk, also a member of the Conservation Commission.

Cedar Circle recently received a grant to convert a portion of the organic cut flower garden to native perennial plants, develop educational materials, and host workshops over the next two years.

While this constitutes essential first steps to a sea change, helping the community understand why Cedar Circle is taking these initiatives is just as important, and so is spreading the word to gardeners and landscapers beyond Thetford. Visit the kiosk!

To quote author Doug Tallamy, "Each of us carries an inherent responsibility to preserve the quality of earth's ecosystems. When we leave the responsibility to a few experts (none of whom hold political office), the rest of us remain largely ignorant of earth stewardship and how to practice it. The conservation of Earth's resources, including its living biological systems, must become part of the everyday culture of us all, worldwide.

Photo credit Li Shen