Blown away! Thetford Selectboard addresses leafblower complaint

Arthur Kahn, who lives in the only house on Thetford Center's Buzzell Bridge Road, recently sent a letter of complaint to the Thetford Selectboard. It began thus:

"Recently, a crew of town contractors spent almost an hour clearing the leaves from the small triangle of lawn where Buzzell Bridge Rd forks onto Route 113. I was on the road walking my dog where the fumes from the three leaf blowers — which also filled my downstairs since I had left the rear-facing (away from Buzzell Bridge Rd) screen door open — were near overpowering. The noise from the three gas-fired machines was at an unacceptable decibel rate. Altogether, it was an unwelcome violation of Thetford Center’s prevailing tranquility."

The letter went on to ponder whether the clearing of leaves from this small area of grass was even necessary. Perhaps it should be discontinued, especially since it didn't stop with the use of three very loud leafblowers.

"... a noisy apparatus attached to a truck vacuumed (the piled leaves) away the next morning, again breaching the neighborhood’s quietude. The total amount of time spent by three workers blowing and then returning the next day to suction the leaves could not have been much less than what 3 people raking the same triangle would have required."

There are two issues here — the noise of power-driven leaf removal and the carbon emissions of these gasoline-driven machines. Indeed, the Town Plan begins with a Declaration of Climate Emergency that requires the Town to adopt all practical measures to reduce emissions.

It is well-documented that lawn and garden maintenance is a significant cause of greenhouse gas pollution. In 2020, gasoline-powered lawn and garden care equipment in the US produced over 30 million tons of carbon dioxide — more than the total emissions from the city of Los Angeles — plus about 68,000 tons of smog-forming nitrogen oxides and 22,000 tons of fine particulate matter. This is equivalent to the pollution from about 30 million cars.

Most lawn equipment uses engines that are very inefficient compared to car engines. And they often use two-stroke engines which burn lubricating oil along with gasoline, hence the bad smell and greater release of pollution. Using such a leaf blower for one hour produces the same amount of emissions as driving a car from Washington, D.C. to Miami, Florida. That's how dirty a two-stroke engine is.

Fine particulate matter may sound harmless, but these ultra-small particles, less than the width of a human hair is size, can penetrate deeply, via the lungs, into the blood stream and are associated with a range of diseases including emphysema, bronchitis, heart attacks and premature death. The blast of air from a leaf blower can achieve 200 mph. It stirs up mold spores and bird and animal feces that are potentially infectious. This is a particular concern to people with allergies, reduced immunity, or other sensitivities.

This hurricane-force gale also kills pollinators and other small creatures that make their winter refuge in fallen leaves. The concern over rapidly declining insects and other small life forms that hibernate in fallen leaves is the foundation of the "Leave the Leaves" initiative. The spectacular Polyphemus moth, the Luna moth, the Great Spangled Fritillary butterfly, and fireflies are all examples of vanishing insect species that rely on fallen leaves to survive the winter.

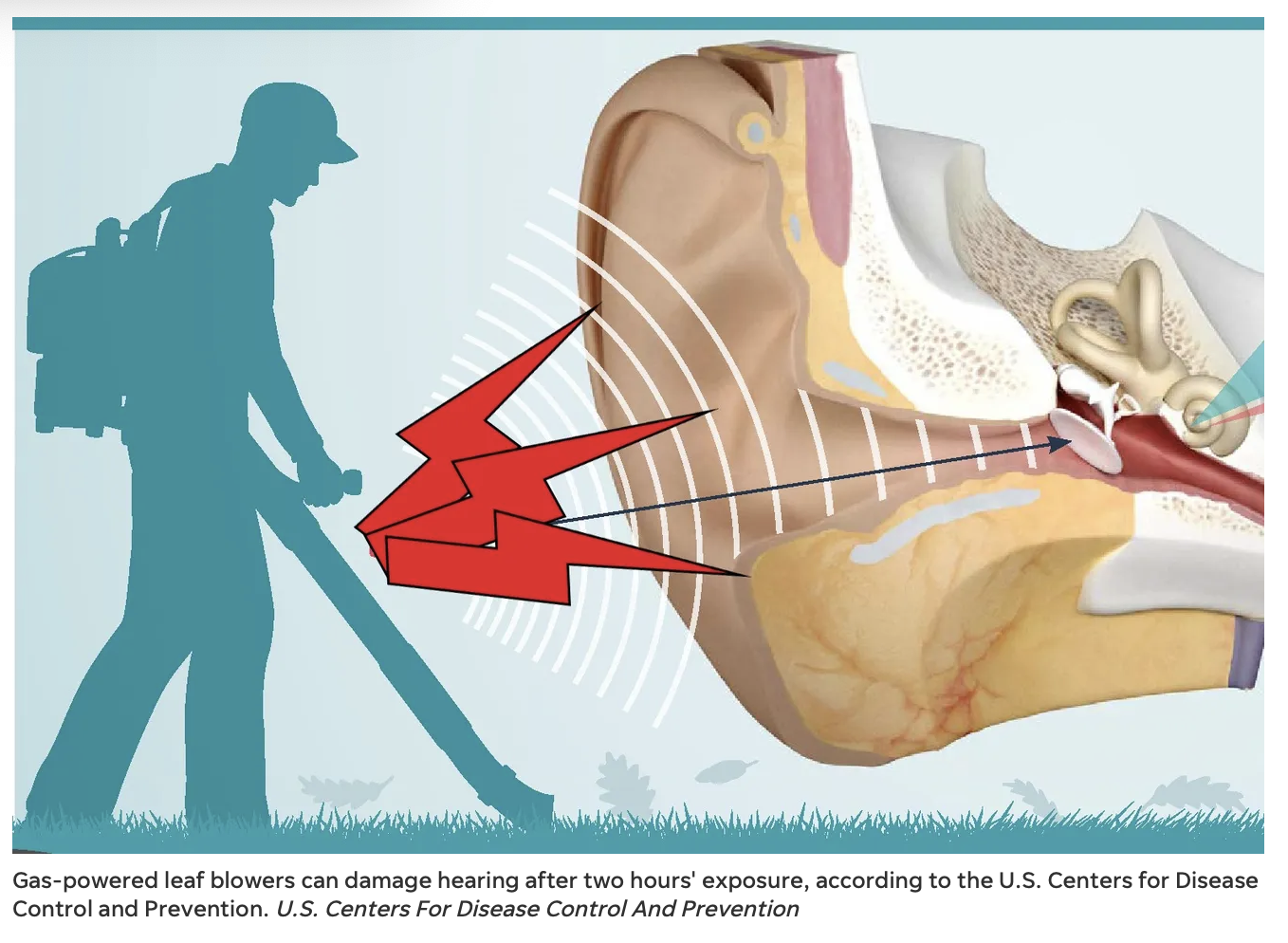

Then there's the noise, which first attracted the attention of Arthur and his neighbors. Typical commercial-scale, gas powered leafblowers emit 95 to 105 decibels measured at the user's ears. Furthermore, the low-frequency noise they emit carries a long way. The routine use of multiple leaf blowers, like the three used to clear one small grassy triangle at Buzzell Bridge Road, exposes not only the workers but people in the neighborhood to harmful and disruptive levels of noise. A two-hour exposure to 90 decibels is enough to cause ear damage, according to the CDC. Repeated exposure to such noise results in hearing damage that has been likened to the brain damage suffered by football players from recurrent blows to the head.

Some suggest that electric leaf blowers are quieter and less polluting. One of the main differences between electric and gasoline machines is that electric ones emit only high-frequency noise, whereas gasoline-powered machines create both high- and low- frequency noise. Low-frequency noise travels further and penetrates walls — even concrete ones — and windows, so it affects multiple properties at once. The actual decibels from electric blowers can be less, typically from 60-70 decibels (about as loud as a washing machine). Note that the decibel scale is a logarithmic scale, so every increase of 10 decibels is tent times louder. Thus an electric blower is significantly quieter than its gas-powered counterpart.

If we must remove leaves, which is debateable, Arthur suggests raking, the traditional approach to corralling leaves. While this can be slow and time consuming, the task has undergone a technological revolution. For instance there are inexpensive, non-motorized gadgets that brush leaves into a bag and can be pushed along quietly. Electric powered versions also exist. And it is much better for the health of the lawn-care employees to use equipment like this, rather than being exposed to noise, particulate matter, and combustion products from gasoline-powered machines.

Arthur also pointed to Burlington as an example of a municipality that acted in 2021 to ban gas-powered leaf blowers by contractors or landowners that service ten or more city properties. By 2022 all Burlington residents were expected to comply by switching to electric machines. The noise from electric leafblowers is regulated to no more than 65 decibels, leafblowers may only be used within certain hours, and only one per 5,000 sq ft on any parcel.

The Thetford Selectboard was uneasy about proposing any ordinance to regulate leafblowers, since enforcing local ordinances has always been difficult to achieve. They agreed it would be easier to approach this issue starting with leafblower use on town-owned property, but no details of how to limit leafblower use and on which properties were elaborated. The main places where leafblowers are used are the village greens onThetford Hill and in Thetford Center, and the lawns around Town Hall and the Timothy Frost building. These green spaces set a tone for their respective villages and are used by residents. Allowing leaves to accumulate might not be viewed kindly. However the triangle of grass at the head of Buzzell Bridge Road is hardly, if ever, used for recreation. The Town Manager agreed to talk to the lawn maintenance contractors about it.

But there is one more lingering question. Why do we need lawns anyway? Lawns originated in Europe to keep the land around castles clear so attackers could be easily seen. They were kept short by grazing livestock. This look was later adopted by the aristocracy to mimic the castle-owners except, in a display of disposable wealth, the grasses were kept short by laborers with scythes. In the U.S., lawns were also adopted by the wealthy upper classes, but for the populus the front of the house usually sported a flower garden with an enclosed yard out back. The landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead was among the first to design suburban neighborhoods where every house had its own front lawn. With the rise in commuting, the immaculate lawn became a suburban status symbol to be viewed by passing drivers, even though it was costly to maintain, needed fertilizer, weedkiller and pesticide application, wasted water, and was little used. Essentially the lawn is a wannabe landscape feature.

Why is imitating suburbia so important? Many of us live here to escape suburbia. Don't we have more informed values than growing unproductive and environmentally damaging, imported lawn grasses? Fescue, a popular imported lawn grass, harbors a fungus that harms insects and prevents them from feeding on it. In essence, lawns are non-native monocultures and biological deserts It would be healthier, less wasteful of resources, and better for butterflies, fireflies, etc. to revert to flower gardens or wild pollinator gardens that support beneficial insects and birds. An informal meadow, seldom mown, can satisfy the desire for open space.The earth would benefit from losing lawns and letting the welcome blanket of leaves settle each fall to shelter hibernating butterfly larvae and more, then eventually decay and fertilize the soil. And there would be no leafblowers.