As ash trees succumb to Emerald Ash Borer, look for the lingering ash

Try not to harvest ash trees before they're infested.

It has, unfortunately, become the assumption that all our ash trees will die due to the invasive Emerald ash borer — it's only a matter of time. Indeed, infested and dying ash trees are cropping up all over Thetford, for instance near the boundary with Strafford. The reaction of some woodlot owners and even forest managers is to cut all the ash trees and cash in on the lumber now while the trees are still ostensibly healthy.

A word of caution here. Ash trees don't show they are infested with ash borer straightaway. The trees decline slowly, and the pest's damage is hidden beneath the bark. In other words, one cannot tell by the exterior of an ash log whether it is infested or not. The rapid spread of ash borer to new locations happens through humans transporting infested wood, be it lumber or firewood. If it weren't for that, the infestation would spread at its natural pace of about 2 miles per year, or 20 miles in 10 years. The pest arrived in Michigan in the mid 1990s, so at 20 miles every 10 years it would have travelled less than 100 miles by 2025 and would not be anywhere near Vermont. As it is, ash borer is now found in 37 US states, the District of Columbia, and six of Canada's provinces. It has killed tens of millions of ash trees, making it the most costly insect in US history, according to the US Forest Stewards Guild.

There are 16 species of ash tree across the US, all susceptible to ash borer. The most important ones are white ash, green ash, and black ash, also known as brown ash. Every species of tree in our forests plays a unique role, providing food in the form of leaves, seeds, buds, etc. to different wildlife species. Ash bark is less acidic than that of other trees and attracts a unique cross-section of lichens and fungi. Ash can also live for several hundred years, allowing their root systems to develop a rich and complex network of soil fungi. The highly-prized morel mushroom is often found in association with ash tree roots. No less than 96 invertebrate species specialize in feeding on ash tree leaves, and about one-third are moths. The caterpillars of moths and butterflies are the main food of baby songbirds. Foresters also appreciate the ash tree because it grows fast and straight, forcing the trees around it to do likewise in the competition for sunlight, thus improving timber quality.

The loss of even one tree species weakens the interconnected nature of a forest and reduces its overall resilience. According to the US Forest Service, five species of North American ash are now considered critically endangered. While the picture looks bleak, there is hope on the horizon. Don't cut them!

Researchers in Ohio noticed that some ash trees were surviving in spite of being infested. They were termed "lingering ash trees." Their resistance wasn't 100% but it was enough that they could be spotted more than two years after ash borer had killed all surrounding ash trees. It piqued the researchers' interest to look for genetic resistance, so they cloned these trees and cross-bred them. Among the offspring were trees with greater resistance to ash borer than the parents. Seed orchards of resistant ash trees are now being developed, with the eventual goal of forest ash tree restoration.

But we won't find lingering ash trees if all the ash trees are cut. In fact, cutting healthy ash trees has proven counter productive. It does not slow the spread of ash borer; rather it probably increases it as the adult beetle needs to fly further to find ash trees on which to lay its eggs. Every ash tree cut could be a potential lingering ash with some resistance to ash borer.

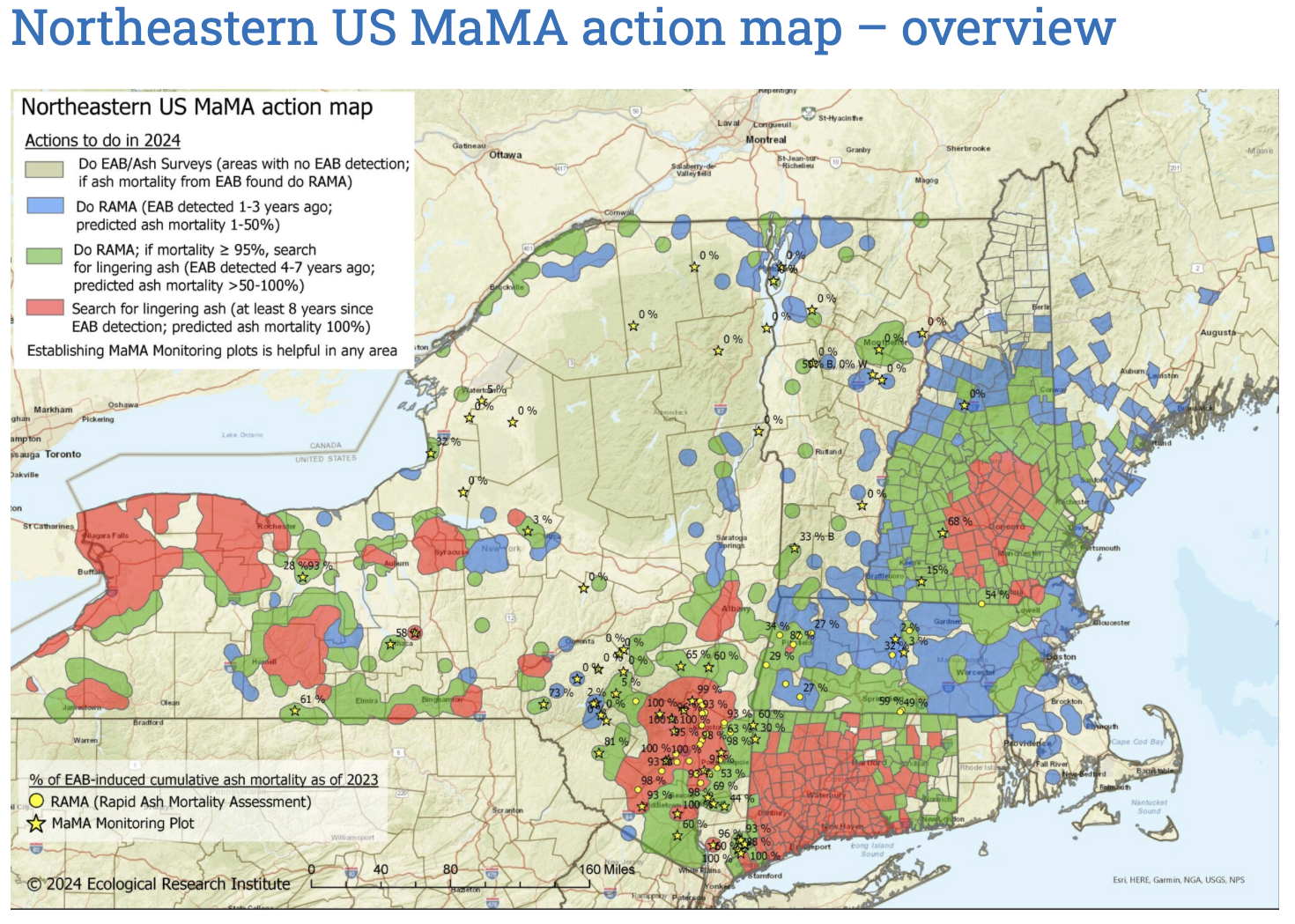

The alternative approach is to let the wave of borer infestation kill all the ash trees, and then, two or more years later, search for mature (over 4" in diameter) surviving trees — the lingering ash! But don't wait too many years, as resistance is not usually complete. Even if we cannot get cuttings to a research facility for breeding resistant trees, we can observe these lingering trees and maybe collect seed from them. Seed from female lingering ash (the trees are either male or female) may pass along some heritable resistance traits. More importantly, lingering ash should be reported to the Monitoring And Managing Ash (MaMA) program – outreach@monitoringash.org – that is directed by the Ecological Research Institute. While searching for these trees might not provide an immediate local benefit as no Action Areas are mapped yet for our part of Vermont, it can be essential to preserving ash species over their ranges in the long term.

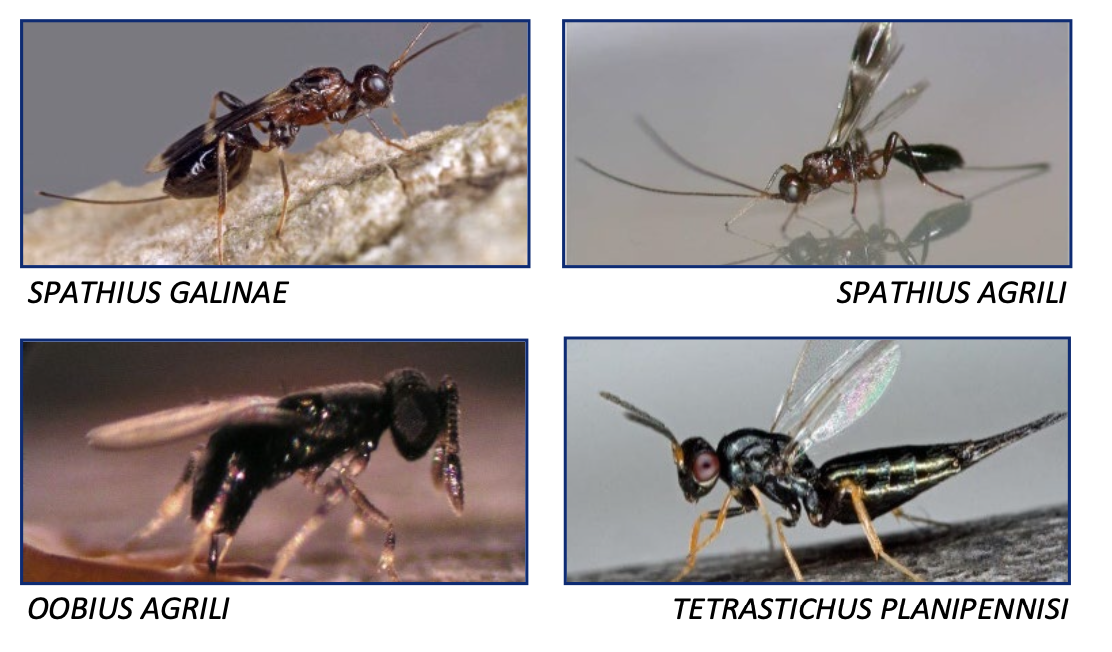

Another hopeful advance is the introduction by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS, of natural predators of Emerald ash borer. Research in the parts of Asia where ash borer is native discovered four wasp species, all tiny, that search out and kill ash borers. They do this by laying their eggs on the ash borer larvae that are feeding under the bark or on the ash borer eggs that are deposited in bark cracks. The wasp larvae that hatch take care of the borer. These wasps are stingless.

The wasps have been released, first in Michigan in 2007 and now in 30 other states and the District of Columbia. In total, more than eight million wasps were released, and they appear to have become established in 22 states, though to what extent is unclear. A follow-up study in Michigan found that wasp introduction killed 20-80% of ash borers in trees up to 8 inches in diameter. In addition, regeneration of ash trees was observed in those areas where wasps were released. APHIS states that the wasps will not eradicate ash borer, but they can be used to manage the pest as part of an integrated pest management approach. APHIS produces the wasps in captivity and calculates the number of infested sites that they can treat, based on Emerald ash borer Program priorities and guidelines

In summary, new biological approaches are in the works. You can still protect an important landscape ash tree with insecticide injections that last about three years, though any creature feeding on the leaves or seeds of an injected tree may also be killed. For this and many other reasons, insecticides won't save the forest. Biological controls and selective breeding of resistant ash trees are our best hope. In the short term, we stand to lose many ash trees. However, losing them as slowly as possible is preferable. If you must harvest ash trees, please observe the guidelines for Best Practices in this link: