A chip off the forest block

When we plan for our future, we will need to consider where we live and how it does, or does not, support our economy, reduce energy use, encourage a sense of community, and protect our natural resources.

At the most recent selectboard meeting of November 7th, the board approved a 1400 ft extension of Jackson Brook Road along what was apparently the route of an “ancient road.” By this action, 125 acres within a large, undeveloped forest area was opened up for what will presumably be a single home and its attendant landscaping. The elongated parcel encompasses a good portion of the Jackson Brook Valley and also extends to the top of the ridge between this brook and the Poor Farm Road valley.

A couple of years ago, on the other side of this ridge in the forest off Poor Farm Road, a new private road named Heaton Hill was approved. One of the subdivisions served by this road now abuts the 125-acre parcel on Jackson Brook.

All of this is perfectly within the law, and there are probably other examples of recent forest land development in town. So, one may ask, why give this any thought?

To elaborate on this question, we should examine the big picture of Vermont’s planning and development goals. At the state level there has been growing concern about forest cover and its integrity. To quote from the Agency of Natural Resources, “For the first time in a century, Vermont is experiencing an overall loss of forest cover. While the exact amount of acreage is hard to pin down, a US Forest Service report indicates Vermont probably lost up to 69,000 acres of forest land between 2010 to 2015. A look at the larger pattern shows that the primary driver of forest fragmentation is rural sprawl. This type of fragmentation occurs incrementally, beginning with cleared swaths or pockets within an otherwise unbroken expanse of tree cover. Over time, new roads, homes, driveways, and yards intrude into connected forest acres. Eventually, the contiguous forest is reduced to scattered and disconnected forest islands surrounded by land uses that threaten the health, function, and value of these forests as animal and plant habitat.”

In response to this concern, the legislature passed The Forest Integrity Act (Act 171) in 2016 “to promote strategies to maintain intact forests in Vermont.” Known as “The Forest Blocks Act,” it requires towns to identify and protect forest blocks and habitat connectors. Act 171 allowed the law governing Vermont Planning (Title 24, Chapter 117; Municipal and Regional Planning and Development) to be amended to encourage and allow municipalities to address protection of forest blocks and habitat connectors in their town plans and land development bylaws.

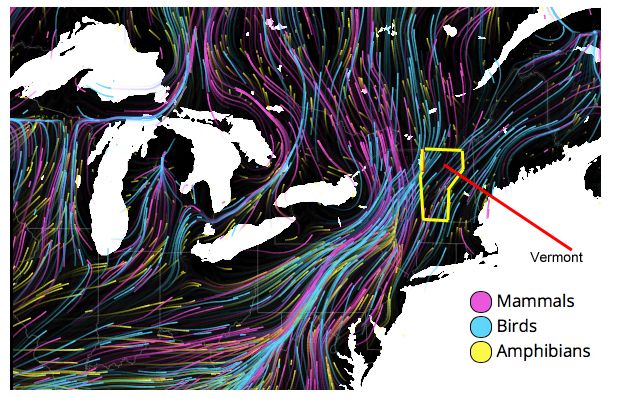

A major portion of Thetford, of which Jackson Brook is but a small fraction, is identified as a High Priority Forest Block in the Town Plan, a document that guides land use. In fact, Thetford is an important piece of the statewide network of connected forest blocks that are, in turn, part of the forests of the northeastern U.S, collectively the largest remaining temperate forest in the world. Large, connected forest blocks accommodate wide-ranging wildlife species and are unsurpassed for sustaining ecological processes and climate resilience. There are nine highest priority connector blocks in town, forming part of a larger swath of highest priority connector habitat running north-south up the eastern side of Vermont. Notably, Thetford is one of the few places where this swath of connectivity abuts the Connecticut River valley and allows wildlife to move east-west, to and from New Hampshire

A house site set back in the woods seems innocuous enough to us humans. In fact, people may believe that a long driveway into a 50- or 100-acre parcel is desirable and less intrusive than a house visible from the road. However, it can be starkly life-altering for species that cohabit the forest with us. Long driveways can break up wildlife corridors that allow animals to move freely between foraging grounds, wintering areas, and breeding habitat. Human dwellings also introduce elements that disrupt natural processes and habitat, such as non-native plants used in landscaping, cats that kill many birds (about 2.4 billion birds a year in the US), dogs that cause avoidance behavior in wildlife, and tree mortality due to root disturbance.

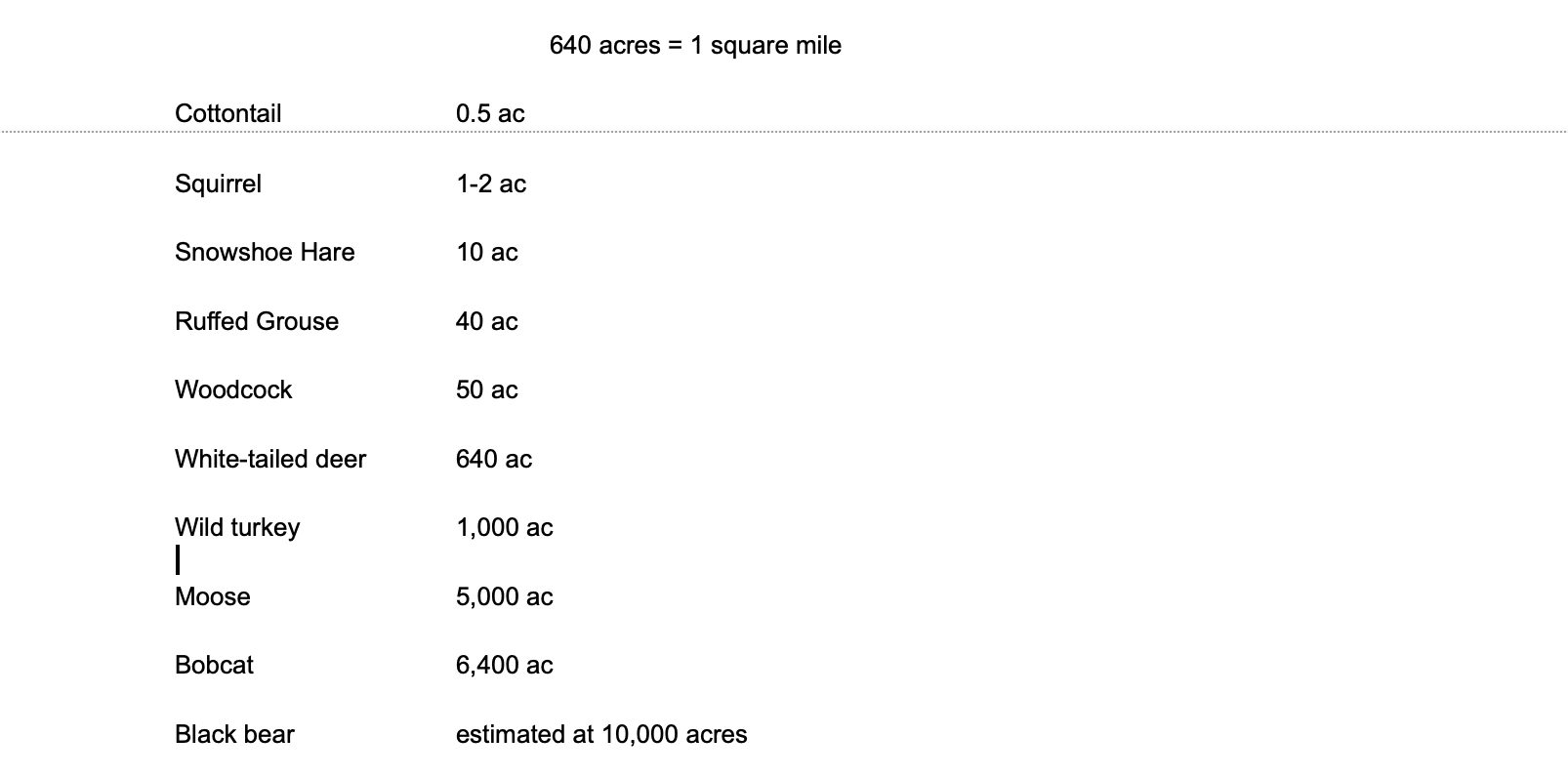

The considerable areas of habitat, including forest, that are needed by some species to sustain their life cycles, can be surprising.

RANGES* OF REPRESENTATIVE WILDLIFE SPECIES IN GOOD HABITAT (*Ranges are defined as areas within which animals habitually move to fulfill their day-to-day activities such as food gathering, mating, and caring for young. It does not include seasonal migration.)

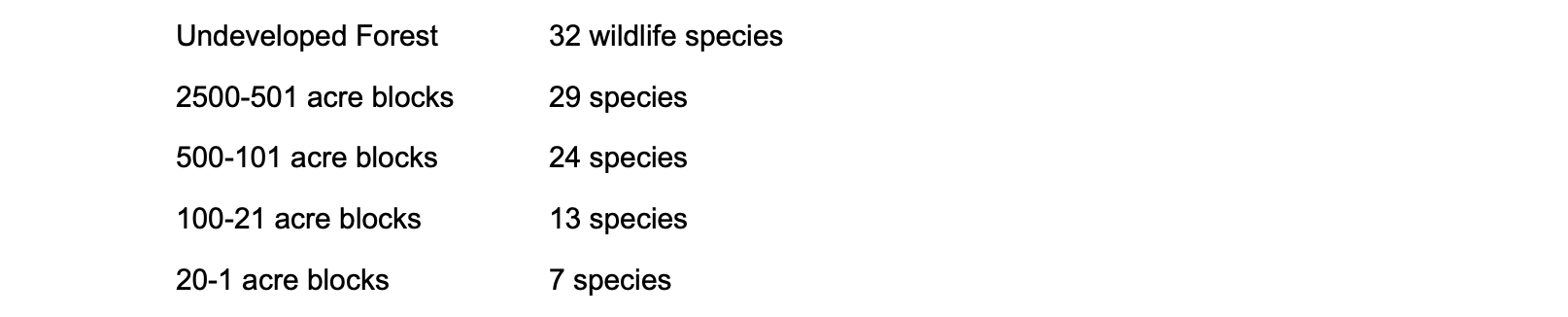

When interruptions in contiguous forest cover divide the forest into smaller areas in a process known as fragmentation, wildlife starts to disappear.

EFFECT OF FOREST FRAGMENTATION ON REPRESENTATIVE WILDLIFE SPECIES

[raccoon, snowshoe hare, porcupine, bobcat, cottontail rabbit, beaver, black bear, squirrel, weasel, mink, fisher, woodchuck, muskrat, moose, red fox, cooper’s hawk, harrier, broad-winged hawk, goshawk, red-tailed hawk, great horned owl, raven, barred owl, osprey, turkey vulture, turkey, garter snake, ring-neck snake, wood frog]

Forest fragmentation also disrupts the connecting corridors that allow the seasonal movements of wildlife. And with climate change already showing its effects, these corridors have become lifelines along which species must relocate in order to survive.

As mentioned, State law allows municipalities to address the protection of forest blocks and connectors through the planning process. How is Thetford doing in this regard? The 2020 Town Plan states that the Town “should” do the following:

The town should minimize forest fragmentation by utilizing cluster housing and peripheral development planning concepts, and use of forest conservation easements.

Under Natural Environment, Pg 61:

“5. The Town should utilize the Vermont habitat Blocks map, the Town Natural Resources Inventory and the Linking Lands Alliance map as the bias for identifying blocks of undeveloped open land and contiguous forest, core wildlife habitat, critical habitats and corridors linking large land tracts and water resources. These should be protected to the fullest possible extent in developments and in Act 250 proceedings.”

And under Forest Blocks, Pg 61: the Goal is “Maintained and preserved large forest tracts that are sustainable biological and economic resources.”

In practice, the town has yet to re-write the relevant bylaws to encourage these initiatives. And “encourage” is a key word, since the Town Plan language does not mandate enforceable protections. It is up to residents and developers to care about the big picture and become educated, perhaps helped by outreach from the Conservation Commission.

In the meantime, forest blocks are coming under increasing development pressure. The shortage of workforce housing is a hot button issue, and climate change is spurring people to relocate to Vermont. However, the State does not advocate carving up forest blocks to alleviate housing needs. Instead, the Vermont Natural Resources Council and Two Rivers Ottauquechee Regional Planning Commission, who put Vermont’s land use laws into action, recommend that towns add new housing according to Smart Growth principles. As stated in the Regional Plan, “We still hope to meet one of the fundamental guiding goals of state land use law, which is to further the traditional pattern of development so as to maintain the historic settlement pattern of compact village and urban centers separated by rural countryside ….

“When we plan for our future, we will need to consider where we live and how it does, or does not, support our economy, reduce energy use, encourage a sense of community, and protect our natural resources.”